‘To Pimp A Butterfly’ marks pivot in Kendrick Lamar’s career 10 years later

Kendrick Lamar's 2015 album, "To Pimp a Butterfly," fuses various Black art forms with politically conscious lyrics that parallel the then rising Black Lives Matter movement. While he's since diverted from political themes in his work, he's still operating under the same agency and artistry he did back then. Sami Siegel | Contributing Illustrator

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

A lot can change in 10 years.

Ten years ago, Kendrick Lamar was different. It was before “Not Like Us” and the Drake beef completely pivoted his career and elevated him to superstar status.

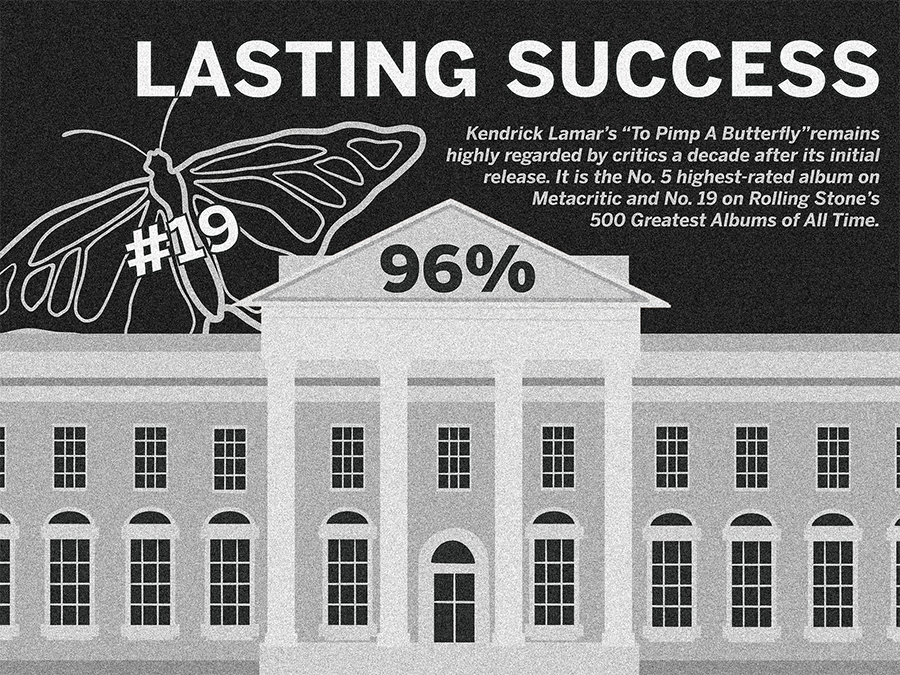

By all accounts, “To Pimp a Butterfly” is a masterpiece. It’s one of the highest-rated albums of all time on Metacritic. It was produced by Lamar in conjunction with some of the biggest names in 2010s jazz, like Thundercat, Kamasi Washington, Bilal and others.

Washington, best known for his own 2015 milestone, “The Epic,” said to Pitchfork in 2017 that “‘To Pimp a Butterfly’ didn’t change the music. It changed the audience.”

Washington was particularly impressed with Lamar’s meticulous process and how he fused the genius of the jazz musicians’ sound together. According to Washington, Lamar “allowed them to be at their best.”

The album also features rap legends from the classic West Coast scene. Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre and even the deceased Tupac Shakur are featured on the album. Lamar brings together various Black art forms, like funk, hip-hop and jazz, fusing them with politically conscious lyrics.

So what does “To Pimp a Butterfly” mean in 2025?

Lamar’s Super Bowl setlist snubbed “To Pimp a Butterfly” and he performed no songs from before 2017, solely focusing on his newer hits. With no songs from his most acclaimed albums — “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” “To Pimp a Butterfly” or “Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers” — it was obvious that Lamar had moved on from his past.

Rather than the streets of L.A. he traveled on “good kid, m.A.Ad city” or the White House he conquered on the cover of “To Pimp a Butterfly,” Lamar now seems perfectly satisfied metaphorically sitting outside Drake’s Toronto mansion and staring him down for 10 months.

But, he’s free to do that. It’s a recurring theme in his career — that Black artistry needs to be free. To demand that Lamar always be political or always perform political music is antithetical to his civil rights and his career’s journey.

His lyrics on “To Pimp a Butterfly” parallel the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of several highly publicized incidents of police brutality, like the murders of Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin. The song “Alright” became a rallying cry for BLM protestors, much like Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” or Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” were for the Civil Rights Movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

“To Pimp a Butterfly” was inspired by his 2014 trip to South Africa, his experience with Black celebrity and the intersection of capitalism, fame and race. In South Africa, Lamar confronted the history of apartheid and racism, and toured the Robben Island cell where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned for 18 years.

Back in the U.S., Lamar was confronted with the reality of racial injustice.

Lamar said to MTV in 2015 that he started the album already knowing where to begin, focusing on feeling “pimped,” or used by the industry. He struggled with his newfound fame and wealth as police brutality unfolded in Black communities across America, a theme that he focuses on in “Wesley’s Theory.”

Joe Zhao | Design Editor

“To Pimp a Butterfly” is a full kaleidoscope of the world as Lamar saw it in 2015. As he rose in the music industry, he witnessed institutional entrapment paralleling institutional violence in his community, which he covers on “King Kunta” and “Institutionalized.”

Lamar also addresses the personal and mental consequences of racism on “u” and “i.” The tracks act as contrasts: “u” is dark, depressive and self-loathing, while “i” is uplifting and an anthem of self-love.

“To Pimp a Butterfly” covers many different topics. “King Kunta” is a boast with hints of Drake shade (“But a rapper with a ghostwriter/what the f*ck happened”), but “The Blacker The Berry” is a brutal indictment of violence in America. “Complexion (A Zulu Love)” explores beauty standards and how race shapes those standards.

Lamar threads these disparate themes with a poem that’s recited throughout the album. The poem sums up Lamar’s journey to South Africa, his revelation there and his wish for his community in America. After reciting this poem in full on “Mortal Man,” Lamar has a discourse with Shakur culminating in another poem.

This second poem explores the relationship between a caterpillar and a butterfly, a metaphor for Black artistry. The butterfly breaks free of internal struggles by shedding light on institutional realities. In effect, this poem sums up Lamar’s views on Black artistry: a Black artist can see past the institutional prisons of poverty and disenfranchisement and offer new concepts to their community.

Lamar executed his agency with the social justice and economic activism of “To Pimp a Butterfly.” Now, despite his pivot away from political themes, he still executes that same agency, performing whatever music he chooses.

It might not be what fans like me, who love his older music, want. I don’t want Lamar to stare at the camera and keep criticizing Drake. I don’t care about Drake enough in any way, negative or positive, to keep hearing “Not Like Us” all these months later. But who am I to say Lamar should adhere to my wishes?

Sam Jackson’s “Uncle Sam” character at the Super Bowl told Lamar that America didn’t want to hear something “too ghetto, too Black.” And Lamar rejected Jackson’s character, and performed “Not Like Us” anyway despite the inherent controversy of the song.

That reflects Lamar’s new stature. He isn’t the “savior” that people labelled him after “To Pimp a Butterfly.” But he’s still a vanguard of free speech and exclusively himself. Lamar’s artistry is still based on that humble ethos that Washington praised to Pitchfork years ago.

Ten years down the road from “Not Like Us,” it’s impossible to say where Lamar, America or any of us will be. But 10 years ago, with “To Pimp a Butterfly,” Lamar changed the audience. And that will continue.