W

hen Joe Viscomi ventured beneath Kimmel Dining Hall, he didn’t know what to expect. Down the rabbit hole, he found a dimly-lit, smoke-filled basement — with the “Godfather of Soul,” James Brown himself, singing and dancing on stage.

Alongside an entourage chanting Brown’s name, Viscomi was so close to the stage that he felt Brown’s perspiration hitting him as the crowd danced shoulder to shoulder for hours.

“If you weren’t dancing, there was something wrong with you, because the music took you off your feet,” Viscomi said.

It was Thursday, May 2, 1985, at Jabberwocky. Known by many simply as “Jab,” the student-run nightclub closed permanently two days later.

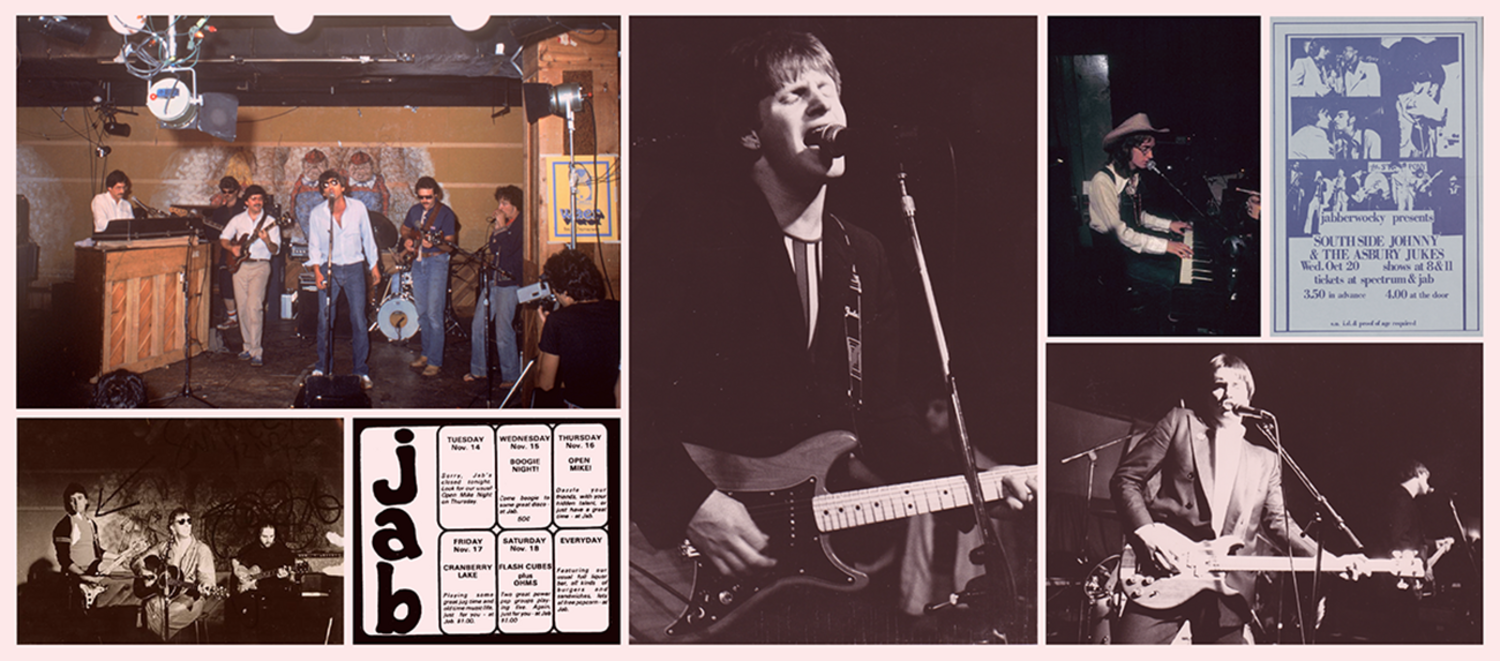

The recent demolition of Kimmel Hall didn’t just remove the dorm from Syracuse University’s campus, but also what was once the home of a legendary campus club. Jabberwocky, named after the Lewis Carroll poem, was a central meeting spot on SU’s campus. It had everything — cheap beer, French fries, loud live music from local Syracuse bands like The Flashcubes and Out of the Blue and sets from national traveling acts like James Taylor and Talking Heads.

Musical and comedic acts performed in front of murals depicting scenes from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Mitchel Resnick, a former SU student, painted the murals while he was on campus. The acoustic panels used to create the murals helped absorb sound and reduce echo in the club.

“You really felt like you were part of a movement,” said Gary Frenay, whose band, The Flashcubes, played at Jab in the 1970s.

Courtesy of John Mangicaro

The Jabberwocky murals when Bird Library had them on display. Each mural featured a different scene from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

After waves of student activism from the Vietnam War, SU students held power over student life and programming, Mike Greenstein said. Since there wasn’t a student union building at the time, SU let University Union operate Jab in the vacant basement of Kimmel Dining Hall. It was a place where students could hang out before Schine Student Center was built. UU members and other SU students oversaw Jab without administrators, Greenstein, a 1970 graduate and former editor-in-chief for the Syracuse New Times, said.

Since Jabberwocky was run by student programmers and managers who had access to a small UU budget, the club didn’t have to make a profit. The students had the leeway to fill Jab with whatever talent they thought was worth promoting.

“We didn’t have to make money,” Joe Bronowich, Jab’s former program manager, said. “We could make our programming decisions based on what was good, what we thought was good.”

Different club managers and programmers each put their own spin on Jab, focusing on different kinds of music or acts.

Bronowich was the program manager at Jabberwocky during the club’s final two years. At the time, he was also a college representative for CBS Records, which helped him book acts like James Brown and a pre-MTV Cyndi Lauper. The decision to close Jab came shortly after the minimum drinking age increased to 21 years old, he said.

But 15 years prior, in 1969, Jabberwocky was just starting out. Jab legally served alcoholic drinks in clear plastic cups, which boosted its popularity as a hub for all students, Bronowich said.

Courtesy of Gary Frenay

The Flashcubes playing at Jabberwocky in the 1970s. As musical acts performed, murals depicting scenes from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland looked on from the wall behind them.

Those who helped run Jabberwocky can still see the club as plain as day: windowless and dark in an era where people could still smoke cigarettes indoors. It didn’t always smell good, Gary Alamin, who worked at Jab while he was an SU student, said.

To create the dive bar atmosphere, students took coffee cans and cut out a hole to use as light fixtures, attaching blue and red gels for the color. A coat of spilt beer made the floor sticky, SU alumna Diana Moro said.

“If you could walk to the door at the end of the night, you could hear your feet on the floor,” Moro said.

Alamin later became a manager for Jab during graduate school. During his time, Jab was open from Wednesday to Sunday, even in the summers. Their Friday happy hour with live music was extremely popular, but to keep business more consistent, Alamin started a happy hour on Sundays called “Die Hard Happy Hour” that ran from midnight until 2 a.m.

Happy hours usually had a line out the door. The fire department advised the club that they could only fit around 200 people there, but Jab often packed in 400 students on those nights, Daniel Block, a student manager from 1977 to 1979, said.

As business got more consistent, Jab offered “Oldies Night” on Wednesdays and “New Wave Night” on Thursdays, where local Syracuse DJs spun tracks. Fridays and Saturdays had live entertainment.

Frank Malfitano, who graduated from SU in 1972, said Jab was the perfect place to hear music on campus as it offered a looking glass for people to see what was going on at SU. Syracuse residents could see folk, jazz and blues artists, like Wynton Marsalis and Taj Mahal, just as Malfitano did.

Malfitano has been producing music festivals for 40 years, and still credits Jab for changing the way he views music. The intimate atmosphere and the variety of music he heard at Jab — what he describes as a “spiritual experience” — shaped his career today as the founder and executive producer of Syracuse International Jazz Fest. Jab inspired him to take risks with SIJF’s programming, he said.

To him, no club has been as “visionary” as Jab.

“I hope, in some small way (with SIJF), I’m giving back what Jabberwocky gave to me,” Malfitano said.

While some remember Jab for its live music and shows, others remember it for the snacks. The beers and fries were 25 cents apiece and the entry cover was typically under $10. Kevin Shumway lived in Marion Hall, across the courtyard from Jab, in 1977. His strongest memory was how delicious the fries were, hot from the fryer and drowned in ketchup — what he called a “munchies-vanquishing treat.”

Back near the bathrooms and dressing rooms, Alamin remembers what he calls the “current events wall,” where students would graffiti messages to their partners and friends or poke fun at goings-on.

Courtesy of Gary Frenay

Jabberwocky even featured a “current events wall.” Students would graffiti messages to their partners, friends or even jokes and jabs at current events.

Jab didn’t only serve students; it also formed a link between SU and the surrounding neighborhoods, Greenstein said. Local bands and national acts, like the James Brown show on Jab’s penultimate night, brought in both students and Syracuse residents, like John Mangicaro, who runs SU’s MakerSpace.

“Even with James Brown, I remember exactly where I was standing,” Mangicaro said. “I was telling (current) students, and they were just blown away that that went on here.”

While the MakerSpace currently operates in Marshall Square Mall, Mangicaro originally started the creative hub in Kimmel Hall in 2013. When SU offered him the opportunity to open MakerSpace, he knew he wanted it to be located in Jab’s old stomping grounds and channel its creative energy. He’s since incorporated instruments like guitars and drums for students to play in MakerSpace so he can honor Jab.

He’s always told MakerSpace visitors about his days at Jab — seeing Talking Heads perform twice, playing with his band and hanging out with friends. He was part of a band called The Drastics that played at Jab in 1979.

“You didn’t realize what a gem it was until after everything was gone,” Mangicaro said.

Most nights, local artists and bands played at Jab to fill the schedule, something that Bronowich said sometimes gets lost in translation. The best traveling bands and national acts played during Sunday happy hours since Jab was the only club open in Syracuse those nights.

Bronowich remembers how he played guitar with his idol, John Cale, at Jab his freshman year, all because Cale needed some extra musicians. Cale was a founding member of the Velvet Underground with SU alum Lou Reed, and he played the last Jab show ever in 1985.

David Rezak, a longtime Syracuse resident, was a local concert booker for Jab in its heyday and went on to be the founding director of SU’s Bandier program. This kind of proximity was something artists enjoyed, he said. When a band came to Jab, they were practically part of the crowd.

That is, unless someone bumped into the mic and it hit the singer in their teeth. Still, the intimate setting was part of what made Jab so special, Rezak said.

“It wasn’t ideal, but it just had such a cool vibe to it that everybody kind of fell in love with it,” Rezak said.

Jab gave artists and bands access to an audience of young, captive college students that was eager to hear new music and new artists. Malfitano said Jab had a knack for spotting the up-and-coming artists, though not all who performed at the venue got famous. He believes this kind of experience is something current SU students are missing out on.

Jab’s music scene reflected the wide variety of tastes during that particular time, Moro said. It also reflected the vibrant, diverse culture that made SU’s campus so great. All students were welcome to hear a plethora of new music they had never heard before — from David Johansen to Aztec Two-Step to Chick Corea.

“Unlike all the other bars that had music in Syracuse, this was ours,” Moro said.

Moro thinks students need a space on campus to hang out and hear live music or new comedians without breaking the bank. But with SU’s ongoing expansion, she’s not sure where a newer version of Jab could be.

Courtesy of Gary Frenay

Jabberwocky closed nearly 40 years ago, on May 4, 1985. It had everything — cheap beer, french fries, loud live music from local Syracuse bands like The Flashcubes and sets from national traveling acts.

Whether or not Jab can be recreated in today’s day and age is unclear. The times are different, and Malfitano isn’t sure if SU’s campus is as accessible today as it was back in the Jab era. The drinking age hike was a significant part of why Jab closed, so not all college students would be able to drink there now, Greenstein said.

But Rezak is a proponent of the contrary: Jab could make it today. What’s needed? The “perfect storm” of Jab — ambitious programmers, new talent looking to get into the public eye, student media and a small, intimate venue, he said.

It’d also have to be programmed with no profit motive to highlight the authentic way Jab’s leaders produced legendary shows in a small space, Rezak said. He believes Jab couldn’t have existed if it had a profit motive, because then it wouldn’t have advocated for students’ true tastes.

Alamin said the focus of a modern Jab would have to be on the attachment to the venue and the music performed there — more of a social gathering than a bar atmosphere. It could expose students to different kinds of music and entertainment, and serve as a bridge between the students and the local community at large, Greenstein said.

Frenay doesn’t know if anything today can do what Jab did. While there are plenty of basement house parties around campus where music flourishes, he isn’t sure they have the same campus-wide impact that Jab did.

“It was just a thing that was of that time and of those people, and it was really a special time,” Frenay said.

When Viscomi recently visited Bird Library, he saw Kimmel’s demolition and felt a little sad.

Some memories have faded in the last 40 years, but the most vivid still remain in the minds of Viscomi and others.

“It deserves to be remembered and celebrated,” Malfitano said. “There has never been anything that even comes remotely close.”

Published on April 10, 2025 at 2:36 am