SU says DPS controls oversight, law enforcement’s access to campus Flock data

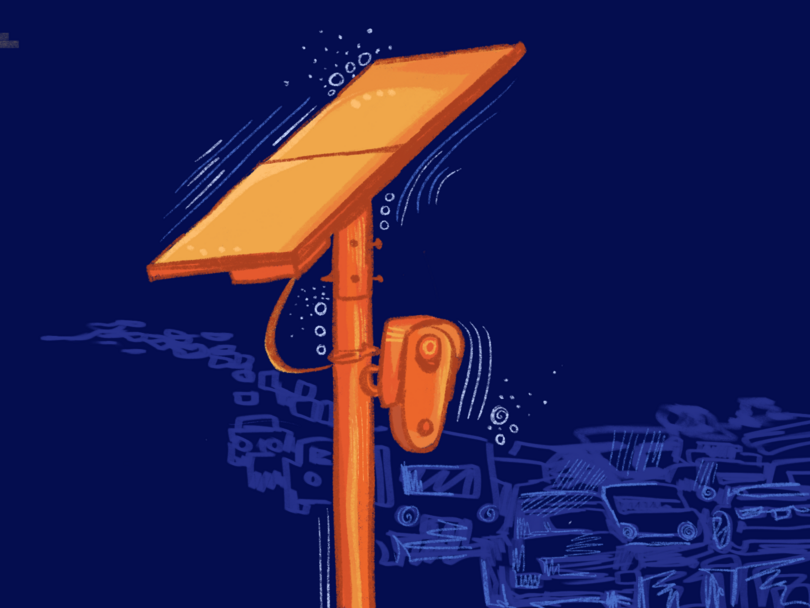

Flock Safety's automated license plate readers, or ALPRs, use cameras to capture car information and run it against a wider surveillance database. The readers have been used to find stolen vehicles or aid in missing persons searches. Hannah Mesa | Illustration Editor

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Flock Safety, the company behind the eight license plate readers Syracuse University installed on campus last month, maintains that its technology does not infringe on the Fourth Amendment, which guarantees protection from unreasonable search and seizure.

Because license plates are government-issued and used on public roads, Flock’s website says the readers comply with the Fourth Amendment. The website also says the technology doesn’t “track people” like a GPS; rather, it only captures images in a set location.

Sidney Thaxter, a senior litigator at the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers’ Fourth Amendment Center, said Flock’s language is “deceptive.”

Case law has found that a one-off instance of using cameras may not violate the Fourth Amendment, but multiple cameras across enough locations could.

“That statement, they’re basing it on a few decisions that didn’t actually explore Flock’s network in particular and the massive reach of their data set that they can dip into,” Thaxter said.

The automated license plate readers, or ALPRs, use cameras to capture car information and run it against a wider surveillance database. The readers have been used to find stolen vehicles or aid in missing persons searches. On its website, Flock says its readers allow users to “tap into the nation’s largest crime-solving LPR network.”

Flock is a $7.5 billion Atlanta-based surveillance company founded in 2017. The company sells hardware and software to cities, schools, businesses and homeowners associations. It also offers other products, including video cameras, drones and mobile security trailers for parking lots.

Using “Vehicle Fingerprint” technology, artificial intelligence-powered software included in all Flock LPR cameras, the devices also identify and store a car’s make, body, color, plate state, whether or not it’s a resident or non-resident plate and other identifiers like roof racks or bumper stickers.

In June, Flock announced the ALPRs could be updated to capture video with an optional no-cost software update, making them more akin to regular surveillance cameras.

Flock consistently emphasizes its “customers own their own data.” But in the past, by opting to access data from other institutions using Flock readers, some of its users — including the Syracuse Police Department — appeared to have made their collected data available to others.

“Law enforcement agencies do not have automatic access to our data,” an SU spokesperson wrote in a statement to The Daily Orange. “Flock has suspended ICE’s access to its system and has also disabled auto-sharing rights to ensure that all clients, including Syracuse University, retain approval rights for any ICE data requests.”

By default, Flock systems store data in a cloud server for 30 days before it’s permanently deleted. Both Flock and SU spokespeople emphasized that SU’s data is not immediately available to other entities unless the university decides to make it so.

“As with all of our customers, if the University chooses to share its data with Syracuse Police Department or another law enforcement agency for public safety purposes, that decision rests entirely with the University,” Paris Lewbel, a public relations manager at Flock, wrote in a statement to The D.O.

National scrutiny

Flock’s system also keeps audit records, which document when users perform a search or access recorded video. Those audits, which require those who access the data to input reasons for their searches, are saved permanently unless local laws require otherwise.

“Only authorized investigators within DPS have access to the system and data,” the SU spokesperson said. “DPS manages oversight, compliance, and any necessary coordination with law enforcement partners.”

The SU spokesperson added that DPS can retain footage for investigations for longer periods of time, “consistent with DPS investigative policies.”

Thaxter said it is difficult to track large-scale instances of law enforcement circumventing official policy to share data with their peers. The reliability of the audit trail requires the person who did the audit to provide an honest reason.

Investigative reporting across the United States, including from 404 Media, found Flock informally allowed the federal government, including U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, access to its audits.

“These are, at this point, incredibly powerful mass surveillance tools that track the movement of every citizen around the country, whether or not you’re suspected of a crime,” Thaxter said.

Flock audit records from the Danville, Illinois, police department found multiple searches labeled “immigration.” Out-of-state law enforcement, including the Florida Highway Patrol and “Houston TX PD,” had also searched the records, the audit showed.

Flock’s legality is case-specific, but a Fourth Amendment concern arises if data from users, like SU, can be added to a network “blanketing” the country, a point made by Thaxter and other legal groups like the American Civil Liberties Union.

“Many police departments neither understand nor endorse Flock’s nationwide, mass surveillance-driven approach to ALPR use, but are adopting the company’s cameras simply because other police departments in their region are doing so,” according to the ACLU.

Thaxter said this data is “incredibly easy to share without anybody ever knowing,” but even institution-specific limitations could still be overcome by a judicial order, like a search warrant.

“As with any government agency, ICE could issue a judicial subpoena to Flock or the University, but that is a standard legal process that exists independently of this system,” the SU spokesperson said.

In June, Illinois Secretary of State Alexi Giannoulias said he would “crack down on unlawful use” of license plate reader records and ordered Flock to stop access to out-of-state law enforcement. This came after Texas police used the technology to track a woman for an abortion-related matter.

Flock said the abortion story was misreported, given that the woman was being searched for as a missing person and faced no charges. Since then, Flock said it adjusted the agencies that had access to Illinois data to comply with state law, and pledged to be a partner in shaping legislation to create a “national model for ethical, transparent public safety technology.”

According to Flock’s website, information for 49 states is available in the national database. Over 5,000 law enforcement entities and 6,000 communities use Flock, the company says.

Introduced in May, New York State Senate Bill S7713, which would restrict the use of automatic license plate reader information, is currently in assembly committee. If passed, it would prevent ALPR users from selling or sharing data with other entities investigating “reproductive health care services or any lawful health care services.”

Over the summer, the Syracuse Police Department realized it had “inadvertently” shared its Flock data with other law enforcement agencies, exposing its data trove to 4.4 million searches. Nearly 2,100 of the searches were labeled immigration related, Central Current reported.

Because the department was able to see other institutions’ records, it opted to share its data in the National LPR Network and made its own information similarly available.

“SPD retains full ownership and control of its data,” Lewbel said. “If SPD chooses to share information with outside agencies, including state or federal partners, that decision is made solely by SPD, and all such access is permanently logged in detailed audit trails.”

City of Syracuse

The city of Syracuse began using Flock surveillance technology in 2023, Lewbel said.

In 2020, before Flock’s contract with the city, Mayor Ben Walsh signed the Surveillance Technology Executive Order, which established new regulations for city offices before installing new surveillance devices.

A working group formed by the order considered license plate scanning technology from March 2022 through March 2023, and found roughly 35% of surveyed Syracuse residents were in favor, while 40% were opposed.

In May 2023, the working group issued a recommendation for qualified approval of SPD’s 26 cameras throughout the city, but it named multiple revisions, including data sharing and retention limits.

“While the intended use of the technology is not to threaten privacy of citizens or use data beyond the scope of the proposed purpose, there are some legitimate concerns and risks, which should be alleviated by the implementation of sound policies, proper training, regular audits, and transparency,” the majority decision read.

Of the 15 members of the working group, 12 — including Sharon Owens, the deputy mayor and current Democratic mayoral candidate — voted yes with stipulation, while two voted against and one abstained.

“First, there is the currently unresolved legal question of whether a broad network of ALPRs violates protections guaranteed by the Fourth Amendment … surveillance by a broad network over time could potentially infringe upon constitutionally guaranteed rights to privacy,” Mark King, a member of the working group, wrote in the dissent.

On May 27, the Common Council approved SU’s installation of two Flock LPRs on city-owned street light poles on the “right-of-way on Waverly Avenue, between Crouse and Walnut Avenues.” The other six LPRs are on university property and were selected with city approvals based on “safety priorities,” the SU spokesperson confirmed.

Legally, there are ways to remove vehicles from these sorts of databases, a process sometimes referred to as “whitelisting,” Thaxter said. But when Flock doesn’t have an easy way to remove entries without directly contacting the data manager, it becomes difficult to do en masse.

Beyond city government, Destiny USA has used the program since August 2023, and said the technology was a “powerful tool in preventing and solving crime” six months later. Flock readers at Destiny scan over 400,000 vehicles per month, according to the report.

Privacy concerns

Lewbel said other universities around the U.S. have installed Flock’s technology on their campuses, including the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Purdue University, the University of California at Berkeley and Temple University.

“The University evaluated a range of options and determined Flock Safety was the best fit given its established use at peer institutions, its presence in more than 4,000 cities including Syracuse, and its ability to meet both safety and privacy requirements,” the SU spokesperson said.

In 2017, the Supreme Court found that the warrantless use of cell-site records violated the Fourth Amendment in United States v. Carpenter, adding precedent to a largely unestablished sector of digital privacy law.

“If you read the pre-existing cases on other technologies like cell site location information and or GPS trackers and you analogize to those, this is a clear violation of the law,” Thaxter said.

Since then, cases in Virginia have found the depth and breadth of Flock’s national network violate the Carpenter precedent. Last year, a Norfolk Circuit Court granted a motion to suppress evidence obtained by a Flock plate reader without a search warrant.

At the time, the city had installed over 170 Flock devices in its jurisdiction.

In United States v. Yang, a circuit court declined to rule on the Fourth Amendment implications of ALPR technology. In Commonwealth v. McCarthy, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled the limited use of automatic license plate readers was not unreasonable.

On Tuesday, Los Angeles County supervisors approved a motion to increase oversight for ALPR data gathered by law enforcement. The motion cited ICE activity and concern that residents “fear that their movements are being tracked, stored, and shared in ways that violate their privacy.”

Flock’s other databases can be used in its Flock Nova product, which consolidates data from ALPRs and other cameras into a single record management system. Beyond Flock, other foreign and American ALPR providers are on the multi-billion-dollar ALPR market.

SU does not appear to be using this technology or any of Flock’s other offerings.

“(Flock) is exploiting an area of law that has yet to be fully fleshed out and decided,” Thaxter said. “They’re exploiting the fact that there haven’t been that many decisions directly saying that what they’re doing is illegal.”