Yasin Willis’ hard-nosed running style fueled by father, childhood workouts

Yasin Willis earned the nickname “Night Train” as a youth player. The name stuck due to his hard-nosed running style, which he's shown at SU. Leonardo Eriman | Photo Editor

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox. Subscribe to our sports newsletter here.

Anwar Suggs didn’t struggle to find a nickname for a 9-year-old Yasin Willis. While playing for the Brick City Lions — a premier youth football organization in Newark, New Jersey — Willis bulldozed anybody who tried tackling him.

Any player who dared cross his path would have to face his wrath. Players ducked out of his way, afraid they’d get run over. It became a common occurrence during Willis’s first summer with Brick City. Before the Lions’ first scrimmage, Suggs — Brick City’s head coach — thought he crafted a good moniker for Willis. He ran his idea by his assistant coaches, and they all co-signed it.

Enter “Night Train.”

“I think he just liked to hurt people when he was young,” Suggs said. “Give him a football and he’d be mean and tough.”

“I love it, man. I feel like it really describes who I am as a running back,” Willis added. “‘What do trains do when something gets in their way?’ They run them over and keep going.’”

The nickname stuck. He gained such notoriety as a youth player in North Jersey that players and coaches didn’t know Willis’s real name. They only knew him as Train. It followed him to Saint Joseph Regional High School (New Jersey), where he developed into the state’s best running back. Punishing blows never stopped being a fixture of Willis’s game. Now, they’re on full display at Syracuse.

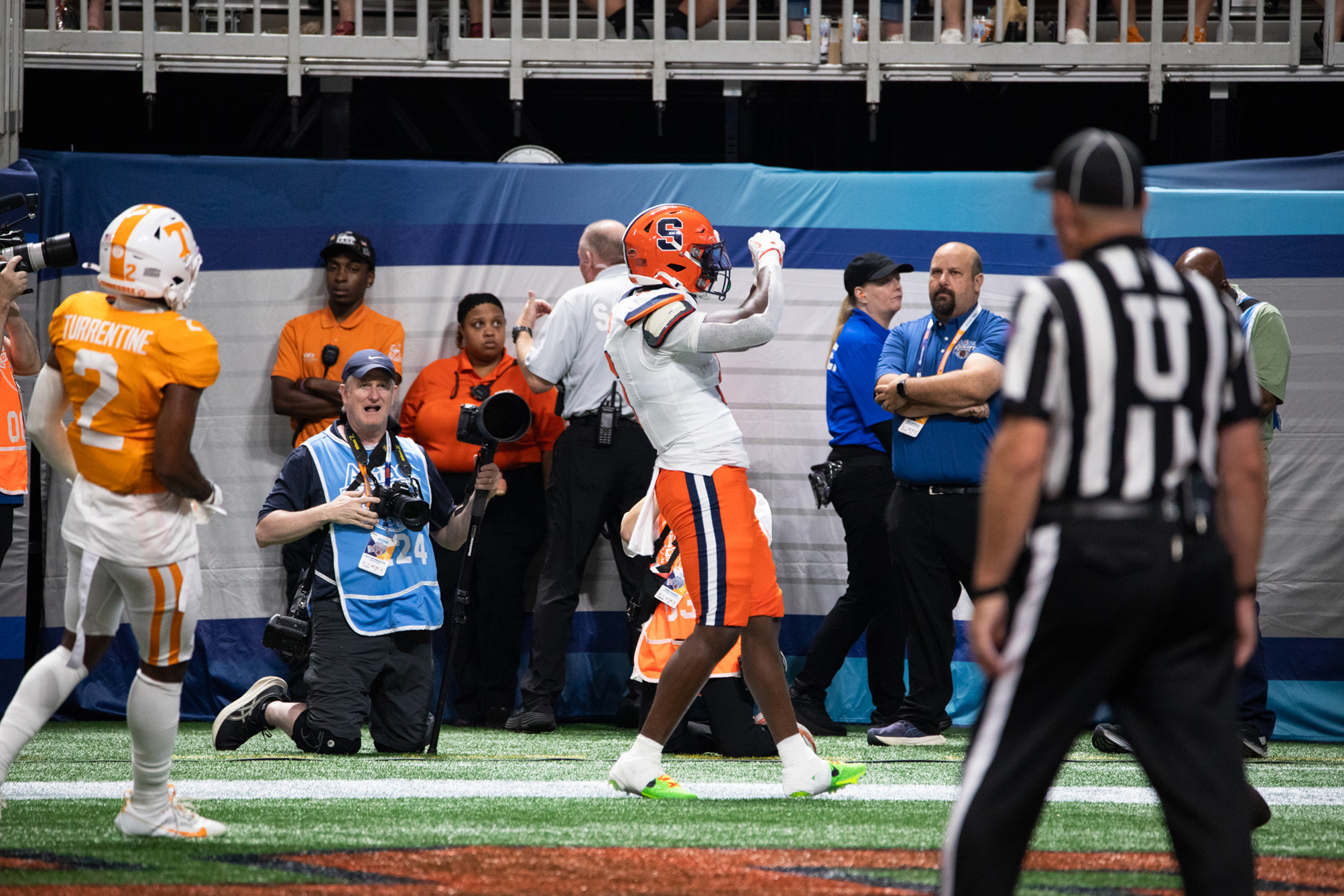

After waiting in the wings behind LeQuint Allen Jr. as a freshman, Willis is ready to be the engine powering SU’s offense. He showed that with a three-touchdown performance in the Orange’s 45-26 season-opening loss to then-No. 24 Tennessee.

The sophomore had 23 carries in SU’s season-opener, just 13 less than his freshman total. That didn’t stop Syracuse head coach Fran Brown from wanting to increase his workload.

“We’re going to make sure we get him the ball more,” Brown said postgame. “He’s the best player on the team from an offensive perspective.”

Replacing Allen Jr. isn’t an easy task. The now-Jacksonville Jaguar was the heartbeat of Syracuse’s offense the last two years, accounting for 25 rushing touchdowns and accruing two consecutive 1,000-yard seasons. Anointing Willis the face of SU’s offense might be a bold proclamation after just one collegiate start. Allen Jr. doesn’t think so.

“I always let him know he wasn’t very far away and his time was definitely going to come,” Allen Jr. said. “It’s his time to shine. I passed the torch to him, and I know he’s going to do great and lead (Syracuse) to success.”

Yasin Willis earned the nickname “Night Train” while playing youth football for the Brick City Lions due to his physicality. He’s shown similar qualities as SU’s new starter. Courtesy of Shanika Willis

But his rise to dominance was far from instant. When Willis was 6 years old, his father, Harold Willis, took him to the East Orange Jaguars, a local youth squad. Willis lasted one practice.

After getting walloped during his first Oklahoma drill, Harold said he didn’t stop crying on the ride home. That told Harold his son wasn’t ready. He told Willis he’d dominate the next time he stepped on the field.

But that wouldn’t happen for three years. In between, Harold molded Willis into Night Train.

The two trained on concrete in the courtyard of their 13th Street apartment. To teach Willis how to manage contact, Harold had him run while his three sisters and his mother, Shanika Willis, swung laundry bags at him. Eventually, Willis was knocking the bags out of their hands.

Harold also made Willis do hundreds of squats with a weighted vest, among other exercises. Willis’s first nickname was “Meatball,” a name given to him by his family due to his chunky frame. That baby fat disappeared after sessions with Harold.

“It was like Frankenstein. I know I was creating a monster, but I had to take my time,” Harold said.

Eventually, Harold took Willis to Brick City. Willis stood out as a power back, sharing the field with future Division I prospects like Jayden Bonsu (Pittsburgh), Adon Shuler (Notre Dame) and Omari Gaines (Stanford). Suggs constantly emphasized the importance of scoring on the first play. Willis took it personally, often plowing through opponents with ease.

“It was always train going wild,” said Brick City assistant coach Nasir Gaines. “That’s what he does. He’s a special kid.”

Willis stayed with Brick City until eighth grade. Then, Harold got a new job that required him to travel frequently and prevented him from training with Willis as often. Harold wanted to provide Willis with structure, steering him away from the wrong crowd. Shanika described their neighborhood as “chaotic,”where carjackings, drugs and other “unacceptable” crimes took place.

Harold had seen promising local athletes miss out on the chance to achieve their dreams because of poor decisions. He wanted Willis to have support from a male figure in his adolescence, something his schedule prevented him from doing.

Sophia Burke | Digital Design Director

Operation Teen Titans was the perfect opportunity. Rahameen Matthews — who Harold knew growing up — helped create the Bergen County-based non-profit, which provides rigorous daily training for inner-city kids from Newark. Players lived with Matthews year-round, who simulated the conditions of a college program with multiple daily workouts, healthy diets and academic tutoring. He also helped players get scholarships to attend elite private high schools in North Jersey.

To give his players recruiting exposure, Matthews had them travel across the country for 7-on-7 tournaments and college camps. It was something Harold and Willis both got behind. Willis previously watched Brick City alumni like Jalen Berger (UCLA) come out as different players after going through the program.

Shanika was less thrilled. She cried at the idea of her only son living under another roof, but she eventually relented.

“Even though it hurt to allow him to go, I knew it was something that would be best for him,” Shanika said. “I knew I had to not be selfish.”

The program was intense. For nine months, players woke up at 5:30 a.m. for a two-to-three-mile interval run. Around 10:30 a.m., they either participated in an on-field skill session or more conditioning. They gathered again at 5 p.m. and capped off the night with a resistance band workout at 7:45.

“I will push them just enough to where they’re about to break, and I back off,” Matthews said. “You are your biggest problem. You’re going to fight yourself more than anybody in this world is gonna fight you.”

Harold gave Willis the foundation. Matthews took it to a different level. Willis started the program at 130 pounds. He entered high school at 190. By his junior year, he hovered around 220 pounds. But more than anything, it was his agility that truly elevated his game.

It started with Willis’s footwork. Matthews critiqued the running backs’ technique through rigorous film sessions. Even if Willis had a successful run, he was called out if his foot placement was off. Once that was down pat, Willis shined in 7-on-7 tournaments. Matthews said Willis could “run routes better than most receivers,” a fact that was overshadowed by his physical running style.

Yasin Willis celebrates a touchdown in Syracuse’s season-opening loss to No. 24 Tennessee. Willis had 91 rushing yards and three touchdowns to lead the Orange. Leonardo Eriman | Photo Editor

Willis was more than ready for varsity by the time he reached Saint Joseph. Though, he had to wait his turn, with future Notre Dame running back Audric Estime — another bruising running back — tearing it up. Once Estime graduated, it was Willis’s time.

“You could pretty much tell there was something different, physically about him,” said former Saint Joseph head coach Dan Marangi. “It was like, ‘Okay, this kid’s got a certain God-given ability that the average kid (doesn’t have).’”

Though Marangi limited Willis’s workload to 20-25 carries per game, his production wasn’t hindered. He combined for 2,156 yards and 26 touchdowns across his sophomore and junior seasons in the Big North Conference, one of the toughest high school leagues in the country.

Saint Joseph running back coach Presley Beauvais watched Willis “put fear in people” with his running style. It was funny for Beauvais to see how Willis became so jovial during pregame warmups. Once the whistle blew, he became a completely different person, Beauvais said. Every run was treated with the same ruthlessness. If he knocked someone over, Beauvais watched as Willis laughed in their face.

“He would talk sh*t,” Beauvais said. “He’s like, ‘I told you I was coming.’”

Willis poured everything into each contest. He took losses personally, to the point where he’d cry in the locker room afterwards.

“It just hit me deep because I’m also playing for people,” Willis said. “When I lost games, I felt like I failed everybody, so I used to hold on to that a lot.”

Harold said he knew where Willis was coming from, but he implored his son not to be as hard on himself. Other Saint Joseph players were going to college even without a football scholarship. Gaining a full-ride was his goal.

Willis began racking up Power Four offers as a sophomore, eventually committing to Pittsburgh prior to his senior season. That changed when Brown was hired at Syracuse four months later. Brown knew Willis through his New Jersey roots. Willis said the coach “understood his background” and his “approach to football,” which led to him flipping his commitment.

Willis approaches football knowing opponents can’t tackle him. During the week, the running back enjoys listening to rappers like NBA Youngboy and Gunna, but he listens to soothing music on gamedays to ensure he remains as calm as possible. Willis said he used to hype himself so much that he’d lose energy before games. He’s more level-headed now.

Once he hears Brown blasting “Closer,” a slow-paced R&B song by Goapele, in the locker room, Willis knows it’s the conductor’s last call.

It’s time to get aboard before the train leaves the station.