R

oy Simmons Jr. extended his arm to reach for his most prized possession. Seated in his wheelchair, it took him a couple tries to unhook it from a nail on a white pillar in his bedroom in Fayetteville, New York.

Once loose, Simmons pulled it to his lap. The 90-year-old gripped the tan hickory wood frame with his frail hands, rubbing the smooth cane-shaped edge. He felt the interwoven leather, which tightly connects to the shaft. He pointed to the purple and yellow mesh holding everything together.

Simmons was grasping his prized lacrosse stick. But it’s not any ordinary one. It was made by his dear friend Alfie Jacques, the legendary Haudenosaunee craftsman.

Next to Jacques’ logo, a date is inscribed into the head.

5-19-23.

Jacques died on June 14, 2023. The stick was his parting gift to Simmons, honoring their tight bond.

“The stick is part of you if you love the game and treat it well,” Simmons said.

Now, Simmons will be honored in Jacques’ name. On Friday, the former Syracuse men’s lacrosse coach will receive the second-ever Alfie Jacques Ambassador Award, alongside another close companion, Oren Lyons — one of SU’s first Native American athletes — for a lifetime of expressing the goodwill and values of lacrosse.

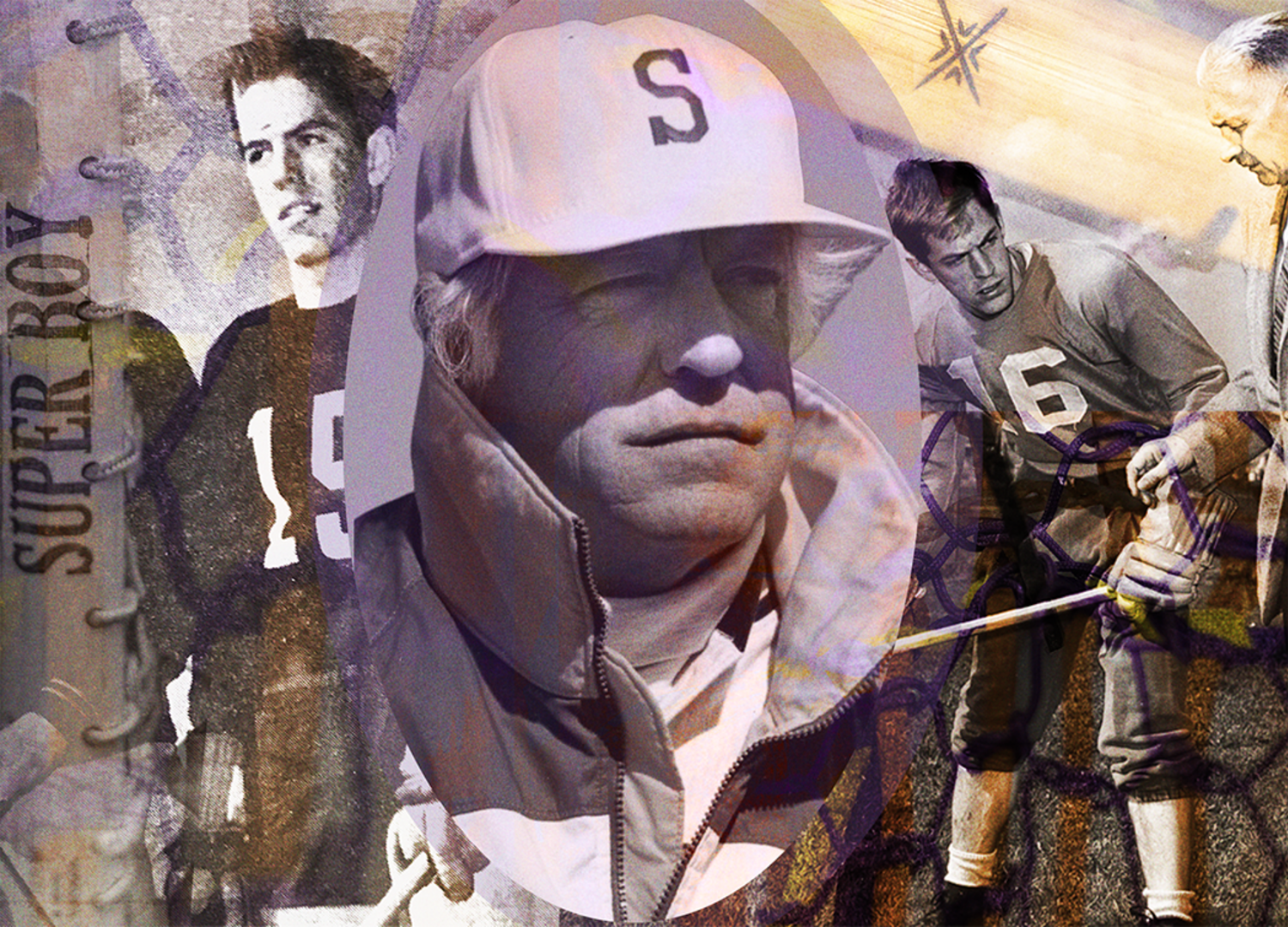

Few people have had an impact on the sport like Simmons. Forget the 16 straight Final Fours, six National Championships and 290 career wins. Simmons has constantly advocated for lacrosse’s Indigenous roots. He didn’t bore his players with X’s and O’s. Instead, he gave them unlimited freedom, a homage to how lacrosse was first played.

“He’s the godfather of lacrosse,” said Robert Carpenter, founder of Inside Lacrosse.

In his home in Fayetteville, Roy Simmons Jr. cradles his friend Alfie Jacques’ wooden stick. Jacques created the stick for Simmons before he died in June 2023. Leonardo Eriman | Photo Editor

Simmons didn’t have a regimented approach. He let his players express themselves on the field. Set plays were foreign. A run-and-gun approach was adopted, during a time when lacrosse tactics were rigid.

His style allowed legends like twin brothers Gary and Paul Gait and Casey Powell to flourish.

The Gaits regularly wowed people with their flamboyant style. Behind-the-back passes and shots that would’ve sent coaches up a wall were encouraged by Simmons.

“He understood the longer that leash was, the more potential a player would actually be able to to exhibit and reach a level that maybe they wouldn’t if they played in a little bit of fear,” said ESPN’s Paul Carcaterra, who played under Simmons from 1994-95.

The Gaits set the stage for Powell nearly a decade later, who embraced a similar approach. They helped Simmons turn Syracuse into a lacrosse dynasty.

His impact is still felt today with Gary at the helm, who tries to instill Simmons’ patented free-flowing nature.

At heart, Simmons isn’t a lacrosse coach. He’s an artist. Literally.

Simmons switched from physical education to fine arts when he attended SU, after Lyons suggested it. Specifically taking interest in West African and pre-Columbian cultures, Simmons designed sculptures and collages.

Take one step into his house, and it’s easy to see his appreciation. Nearly every part is covered with his 60-year-old collection.

Various artifacts hang in the kitchen and dining room, from masks and pottery bowls from Mali and Ghana, and Peruvian clothes, all of which were collected during Simmons’ travels. He wheels around his living room and bedroom as if he’s a tour guide in a museum.

Lacrosse memorabilia, including wooden sticks, is mixed in, four of which hang on a door connecting the kitchen and living room. A picture of the 1957 Syracuse lacrosse team sits next to them, which shows Simmons standing beside Lyons and another close friend, Jim Brown, arguably SU’s greatest athlete and an all-time great National Football League running back.

On the wall, Roy Simmons Jr. points to a picture of the 1957 Syracuse lacrosse team that includes himself, Jim Brown and Oren Lyons. Simmons was a part of the undefeated national championship squad before he won six titles as SU’s coach. Leonardo Eriman | Photo Editor

“I probably have too many interests,” Simmons said. “People used the words schizophrenia. I’m here, I’m there. I probably should have put all my eggs in one basket.”

“But my interests were too diverse.”

Simmons’ attraction to native culture stems from growing up near the Onondaga Nation. When he played at SU (1956-58), his father, Roy Simmons Sr., took his teams to the reservation to play box lacrosse. The reservation’s team also scrimmaged Syracuse at Archbold Stadium.

Once his Syracuse playing career concluded, Simmons continued playing box lacrosse on the reservation. Jacques’ father, Louis — also a stickmaker — was the goalie for Simmons’ all-white team made up of former college players in the region. Alfie constantly roamed the stands.

Eventually, the two bonded. Alfie started making sticks when he was around 30 years old, before plastic sticks rendered that industry almost obsolete.

Back then, if players needed a wooden stick, they traveled to native reservations. Simmons said he respected the artistry, a process that takes around a year. He can recall every step in the crafting process, from cutting down the tree to steaming the wood and curving its head. No two sticks were the same, much like Simmons’ art.

Now plastic lacrosse sticks are cookie-cutter. He said he feels they lack authenticity, and the connection has dwindled. Every wooden stick has a different feel, according to Simmons. It’s the player’s job to become comfortable with it.

“You pick out a wooden stick that you feel good about, and the balance of it and the feel of it in your hands is really special,” Simmons said.

Simmons remembers sleeping with his wooden stick growing up. When traveling to games as a player, everyone held their stick proudly beside them. It represented the game’s origin and spiritual background.

It’s the oldest sport in North America. The Haudenosaunee created it in the 12th century to give thanks to The Creator.

Labeled “the medicine game,” lacrosse is meant to bring healing. Boundaries were endless. Fields stretched for miles. Sometimes games lasted days. Peace was even brought between the five nations at Onondaga Lake 1,000 years ago, through the game.

Simmons relayed that history to his players. Most didn’t know what it truly meant to play lacrosse or where it actually came from, he said. Few were aware Native Americans invented the sport. That changed with Simmons.

He reintroduced the tradition of bringing players to the Onondaga reservation to immerse them in the culture. He also spoke about the background of lacrosse, weaving it into pregame speeches and harping on the game’s deeper meaning.

“You had to respect the culture of the game and the opportunity to play lacrosse,” said former SU player Ansley Jemison, a member of the Seneca Nation of the Wolf Clan. “You’re playing for the joy of the creator. Roy understood that.”

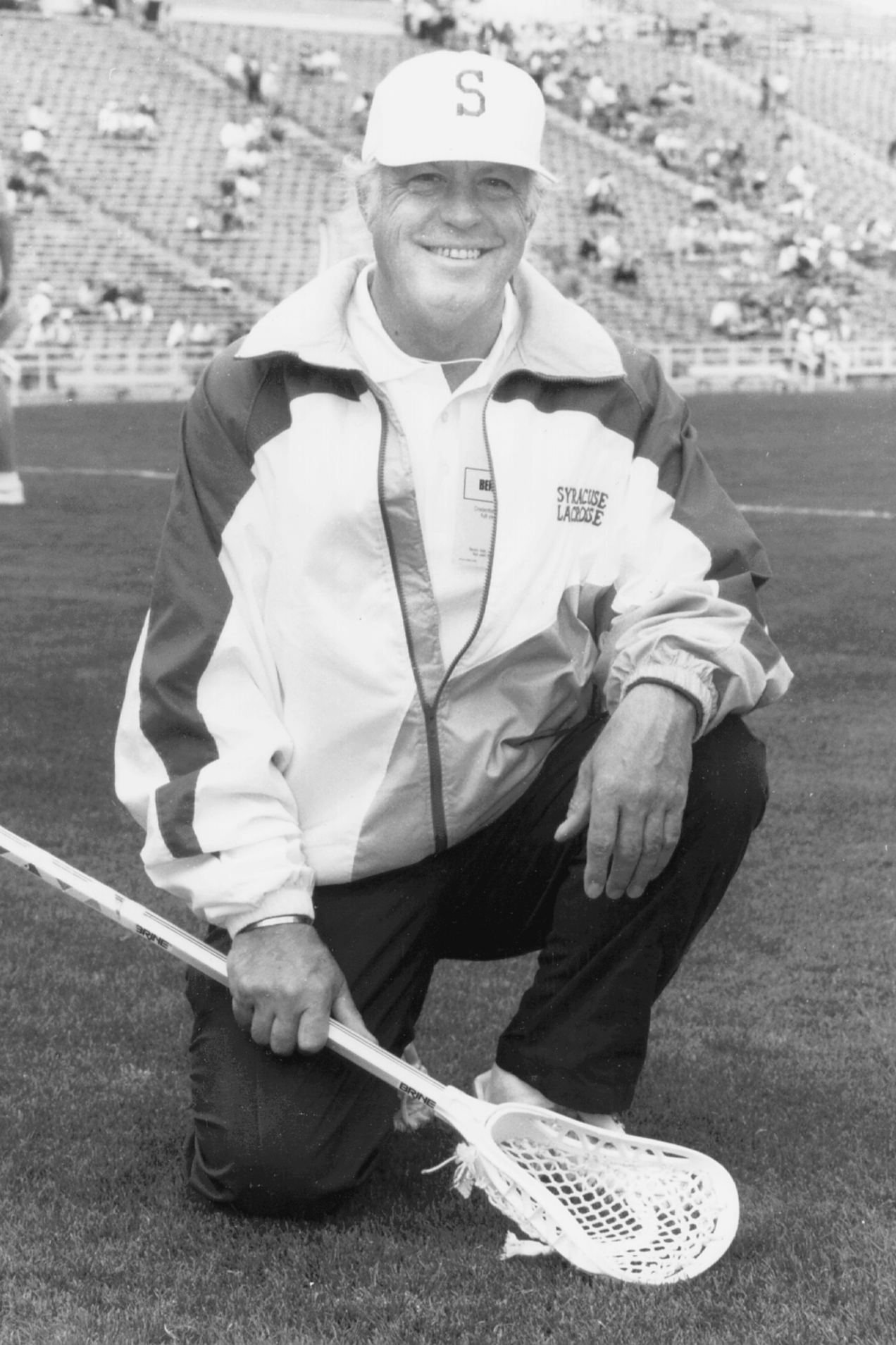

Roy Simmons Jr. gets ready to coach a Syracuse lacrosse game. Simmons spent 28 years as the Orange’s head coach, where he finished with a 290-96 record. Courtesy of SU Athletics

Jemison felt comfortable with Simmons. He previously had Native players like Freeman and Bossy Bucktooth and Travis Solomon — SU’s goalie during its 1983 National Championship — play for him. Jemison faced academic challenges at Syracuse as he struggled to adjust to the new environment, a common experience among other native players.

Through his shortcomings, Jemison knew Simmons would support him. If Jemison had to take time off and go back home to his reservation, Simmons understood. He knew Natives had a completely different way of life and didn’t question it, Jemison recalled.

That knowledge and reverence for lacrosse stemmed from his talks with Lyons — a Haudenosaunee faithkeeper of the Wolf Clan — and Jacques. Simmons referred to Jacques as his “stradivarius,” a homage to Antonio Stradivari, the 18th-century violin artisan.

They had breakfast together at least once a month for years. The two could talk for hours, Simmons said. Jacques was diagnosed with kidney cancer in 2015, but his health took a turn for the worse in 2023. Jacques started paying weekly visits to Simmons’ home before he passed away in June.

“It left a big hole in his heart,” said Simmons’ son, Roy Simmons III.

Relationships were key to Simmons throughout his coaching career, which began in 1971. Soon after taking over for his father, Syracuse implemented budget cuts, leaving Simmons with no scholarships, little equipment for his players and no overnight travel for games.

To improvise, Simmons introduced his run-and-gun style. He recruited local football and basketball players, who lacked stick skills but were pure athletes. It was ugly early on. Syracuse went 26-35 during Simmons’ first five seasons.

“The community really backed up on him,” Roy III said. “There were pockets of people in town that were talking about ‘How do we manage this and get him out?’”

Simmons said he never felt the pressure. He spent his spare time in his backyard art studio. It was his escape, a place nobody could tell him what to do.

He entered art contests, traveling to New England, New York City, Rochester and Buffalo. In the offseason, he visited countries in Africa and South America to learn about different cultures. While other coaches became consumed by success on the lacrosse field, Simmons varied his interests.

Some might call it too laid back, but the coach wasn’t influenced by anyone. Much like his sculptures, he molded his teams the way he wanted. Eventually, his fortunes flipped.

“He went literally from the outhouse to the penthouse,” Roy III said.

Key recruits like John Desko and Kevin Donahue — both of whom later became assistants under Simmons — along with other central New York products, helped turn things around. Three straight NCAA Tournament appearances from 1979-81 were the impetus for the most dominant stretch by any lacrosse program ever.

Simmons wasn’t a tactical mastermind. All he asked was for his team to play fast and free.

Simple concept, right?

It revolutionized lacrosse. Defenders crossing midfield to initiate attacks was previously unheard of, according to former Syracuse longpole Jeff McCormick. That was a staple of Simmons’ philosophy. If you could make a play, go and do it.

“The lacrosse field was a blank canvas for him,” Carcaterra said. “His paint brushes and his colors were his team, and he didn’t often know what that next stroke would be.”

Former Syracuse head coach Roy Simmons Jr. poses on the field before a game. Simmons’ tactics were unlike any other coaches’ at the time, which included employing basketball and football players. Courtesy of SU Athletics

Too stuck in their ways, Roy III said opposing coaches hated it. He watched coaches chew out their players for the slightest mistake. Simmons took the soft approach. He had a different way to bring out the best in his players.

During the 1983 National Championship, Syracuse trailed Johns Hopkins 12-5 in the third quarter. Solomon was struggling in net, and McCormick started to doubt him. Simmons pulled McCormick aside. The captain raised questions about Solomon. Simmons quickly shot him down, telling him, “Sometimes you have to dance with the girl you brought to the dance.”

It was classic Simmons. In the biggest moment of his career, he cracked a joke.

“Talk about a gutsy call,” McCormick said.

Syracuse scored 10 of the next 11 goals, claiming a 17-16 win for the first of six national championships in 13 seasons.

Any former Syracuse player will recount similar tales. Powell remembers sitting on the bus before a Final Four. Senior players blasted rap music on the speakers. Simmons arrived and replaced it with classical music. Powell and his teammates gave each other puzzling looks.

The music stopped after a 15-minute ride to the stadium.

“Do you know who that is?” Simmons asked. Nobody answered. “That’s Mozart. He was the best at what he did. Now go be the best at what you do.”

The bus exploded with excitement.

“Everybody that played for him just absolutely loves him,” Powell said. “He just had this way of connecting with the players, individually and as a team. You played harder for him than you would for anybody else.”

Simmons never stopped teaching. He took his teams to museums during road trips. On long bus rides, he replaced movies like “CaddyShack” and “Slap Shot,” with “Lord of the Dance.” It was all part of the Simmons experience.

Everything had a purpose. From talks before practice to pregame lectures, dubbed “Simi Speeches” by Donahue, Simmons always commanded the room. He quoted philosophers, authors like Mark Twain and sportsmen like Satchel Paige.

It didn’t always immediately resonate with players. McCormick remembers warmup laps where players asked, “Did anyone understand what he just said?”

Sometimes it took years for players to make sense of what Simmons said. Once they raised families and reflected on his messages, Powell said they grew an appreciation for what their coach tried to communicate.

“Roy tried to take a bunch of young men and turn us into a real team and essentially make us all not just smarter, but wiser,” McCormick said.

Despite being confined to a wheelchair, Roy Simmons Jr. admires his special wooden stick. After he retired from coaching, Simmons focused on art before back surgery forced him out of the studio. Leonardo Eriman | Photo Editor

In moments, Simmons was more direct. Powell remembers the coach writing Psalm 118:24 everywhere. It read, “This is the day the Lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it.” Simmons wasn’t a religious person, but the words resonated with his core message of expressing yourself on the field.

Simmons always knew what buttons to push. The quirky remarks, the nonchalant nature and the lack of tactical emphasis worked. Syracuse was a well-oiled machine from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s. Its spot at Championship Weekend was a divine right.

The success never went to Simmons’ head. He didn’t change how he coached and trusted his judgment. Rarely did it backfire. Though during one of his most crucial moments, it did.

Before Syracuse’s 1998 Final Four showdown against Princeton, Simmons told Powell he was going to retire. It caught the four-time All-American off guard. Powell knew Simmons was trying to motivate him. It did the opposite. Instead, he went scoreless for one of the only times in his career. The Orange lost by one goal.

At 63 years old, Simmons’ coaching career ended. Looking back, he feels he retired a little early, but as he’d done his entire career, nobody could change his mind.

“I wanted to spend time and retire under my own terms, not the terms of what I was expected (to do),” Simmons said.

Retirement gave him time to focus on his art. Simmons continued his work until a major back surgery and subsequent infection in the hospital hindered him a few years ago. He lost the strength in his legs, and while rehabbing, he ran into another physical setback. Now Simmons is confined to a wheelchair.

He passed the studio off to his son, Ron. Simmons is protective of the space, letting few people inside. One day, he hopes to return.

Without it, there’s a void that’s becoming harder to fill.

Art was crucial to his life. So was lacrosse. The two were interchangeable. He’ll always be remembered for his impact on the sport.

Simmons taught the history of the game. Little did he know, he’d become an essential part of it.

Design by Ilana Zahavy | Presentation Director

Published on September 10, 2025 at 11:20 pm