Opinion: What a debate club meeting taught me about our political discourse

Productive political debate’s been blurred with conniving ideology battles. Our columnist urges exposure to different perspectives to adapt to approaching debate without silencing opposition, which yields productive results. Leonardo Eriman | Photo Editor

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

On Sept. 23, the Syracuse University Debate Club attracted about 30 aspiring debaters and me for its second meeting. I sat in the back with a notebook, prepared to learn how to disagree better.

Haley Greene, SU senior and the club’s vice president, acted as a judge for the debate. She listened attentively to each argument. She took notes. I took notes, too, as I tried to resolve my question: where do arguments begin to fall apart?

I thought of the question around two weeks before the SU Debate Club meeting, when political activist and Co-Founder of Turning Point USA, Charlie Kirk, was killed during a public debate at Utah Valley University. The incident was front-page news for days. It rattled Americans, regardless of party affiliation, for various reasons.

In the wake of Kirk’s assassination, the United States confronts a unique opportunity to transcend partisanship and establish a healthier set of norms for political discourse. An effective culture of debate and argument can exist – but first – Americans must identify where our disagreements start to go wrong.

Our understanding of argumentation is simplistic in 2025: the intention of political discourse is to force our opponent to forfeit rather than understand their perspective.

Like anyone else, I see the appeal in watching videos showing the moment someone I agree with wins an argument annihilation-style. But debate must be more complex than that.

Diminishing a war to its decisive battle ignores the objectives and intentions of its adversaries. Similarly, diminishing a debate to its outcome contradicts its intended purpose: to better understand each other through an exchange of ideas. It only polarizes either side more and, in turn, paves a path to increasingly extreme thought.

Kirk’s style of debate engaged many young people into the world of politics. However, through the medium of short-form video content, he reduced serious issues to mere clips and one-liners.

“Prove me wrong” was the tantalizing statement he used to attract challengers to argue against him. The cost of losing was the out-of-context moment posted on TikTok.

The command has infiltrated discourse and now represents argumentation and debate in every facet of American life.

SU Debate Club’s meeting centered on the question, “Should comedians and entertainers have absolute freedom of speech in their acts?” The club’s communications director, SU junior Colin Harkins, rolled a die to determine each group’s position defending either the affirmative or the negative.

Both inexperienced and seasoned debaters prepared their arguments. I observed a freshman assigned to the negative contort her face while researching facts in support of a thesis she personally disagreed with.

A good debater rejects what’s comfortable. If a debater has the will to win, they relish in the process of stretching out of their comfort zones. They embrace how the simple act of rolling a die decides their position – even if it conflicts with their own convictions.

“Debate should be uncomfortable,” I wrote in my notebook.

Our arguments go wrong before they start because we’ve gotten too comfortable in our mindsets. But comfort in stagnant mindsets doesn’t make us more morally upright. It only makes it harder to form an argument that resonates with our adversary.

At the end of the debate, Greene offered her notes on how each group could improve. She highlighted the negative’s rebuttals and praised one of the debaters for preparing a quick, fact-based counterargument.

“Good debaters alter their strategies,” I wrote.

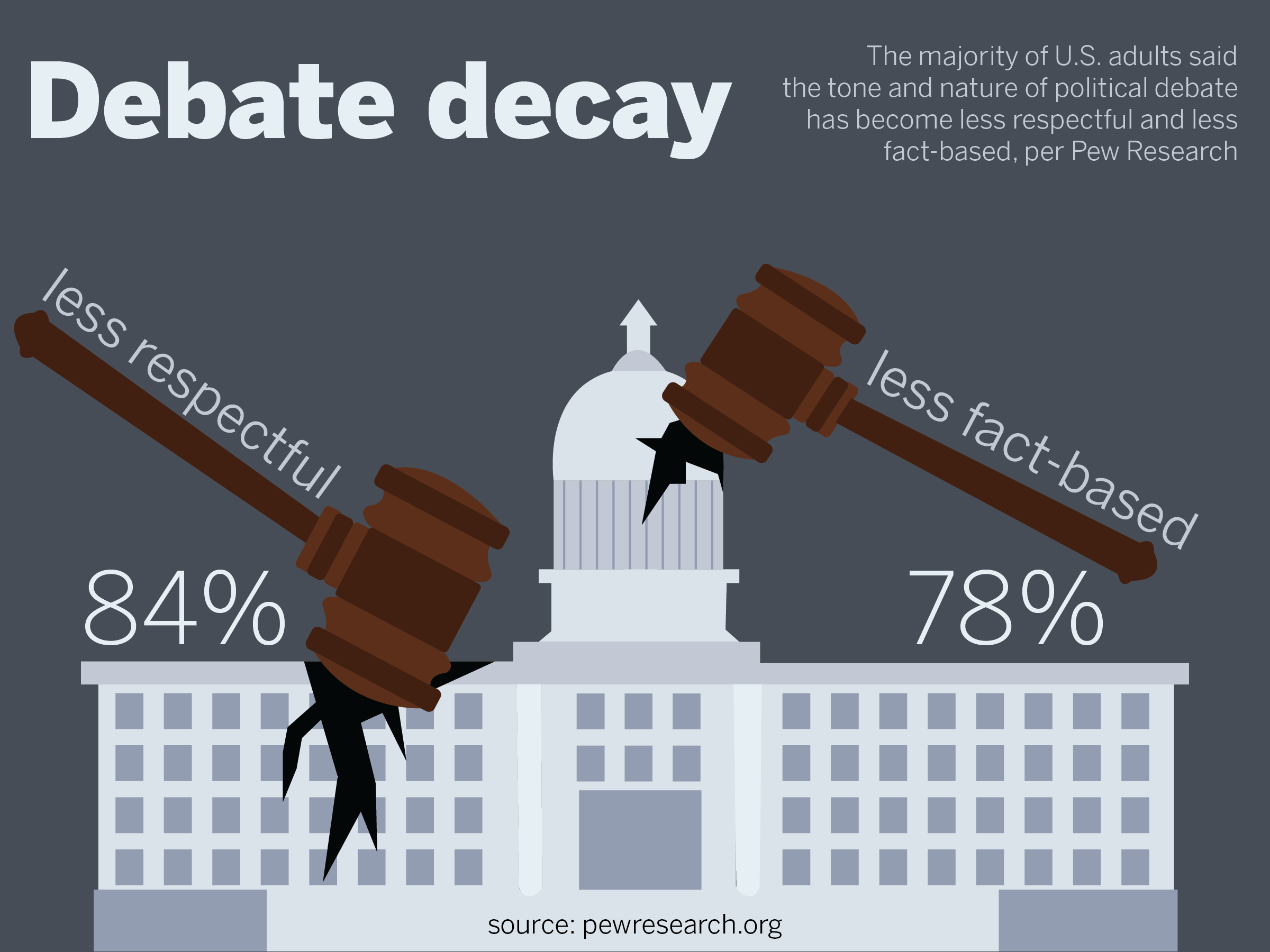

Zoey Grimes | Design Editor

Over time, we’ve collectively stopped trying to pivot our methods of changing the minds of others. Instead, we parrot the same approaches and get upset when our opponents are still unreceptive. But as our conversations escalate, our emotions overwhelm our rationale and we lose the ability to adjust our strategies.

We learn how to behave through trial and error in our childhoods. For example, two kids are playing in a sandbox. One kid won’t share the shovel, so the other throws a punch. This leaves one kid crying and the other being sent to the principal’s office, where they’re forced to reckon with their failed strategy of persuasion.

With time, we begin to learn the art of argumentation. We use tactics that work and leave behind the ones that don’t.

It’s easier when we’re young: our objectives are often simple, so our methods of achieving them are often effective.

By our teenage years, we begin to enter the political world in one way or another, feeling pressured to translate our internal values into political stances. But there’s no guidebook on how to enter this more serious world of debate. In the span of a year, your most serious topic of debate could shift from whether or not pancakes should be an acceptable dinner food to if the U.S. has an obligation to provide universal healthcare.

This enhanced complexity of conversation becomes overwhelming. Younger generations turn to the internet in a desperate attempt to align themselves with a faction. It’s a double-edged sword — while we have access to unlimited information, our algorithms often keep us in spaces which infrequently challenge our developing way of thinking.

“The reason Americans have lost touch with the ability to have debate is because of the echo chambers that exist online, and honestly, these echo chambers exist everywhere. It has become so easy to place yourself in environments where you’re surrounded by people who think the exact same way as you, all the time,” Harkins told me.

The U.S. political climate in 2025 has reversed our maturation as effective debaters. The norms we became accustomed to through development no longer apply. We are once again children in the sandbox, hitting each other out of frustration, and this time with more power and influence.

Our emotions have become so tightly bound to our worldviews that our disagreements often escalate to the point of hatred and prejudice, making productive conversation impossible. When we reach this level of divisiveness, our argumentation is inherently weaker: we cherry-pick our facts to fit our narratives, and often end up contradicting our own value systems as we presume our opponent’s stance before hearing them.

As an opinion columnist, I spend time each week attempting to persuade readers of things I believe. The process of argumentation is as internal as it is external — I must first challenge my own perspective to convince you to reconsider your own. In operating under the strategy formal debate employs, I find this much easier.

Maya Aguirre is a senior magazine news and digital journalism and history major. She can be reached at msaguirr@syr.edu.