Amid new format proposal, McIntyre says college soccer needs to ‘grow and evolve’

Syracuse head coach Ian McIntyre weighs in on the new proposed college soccer format, which would include promotion and relegation. Meghan Hendricks | Daily Orange File Photo

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox. Subscribe to our sports newsletter here.

On Oct. 16, the NextGen Soccer Committee, a 17-member group formed by the U.S. Soccer Federation, released a white paper detailing plans to “adapt to meet the rapidly changing context of both domestic soccer and college athletics” by the 2026-27 academic year.

Ahead of this summer’s 2026 World Cup hosted by Canada, Mexico and the United States, U.S. Soccer has taken steps to ensure its youth and collegiate soccer setups are definitive pipelines to the U.S. Men’s and Women’s National Teams.

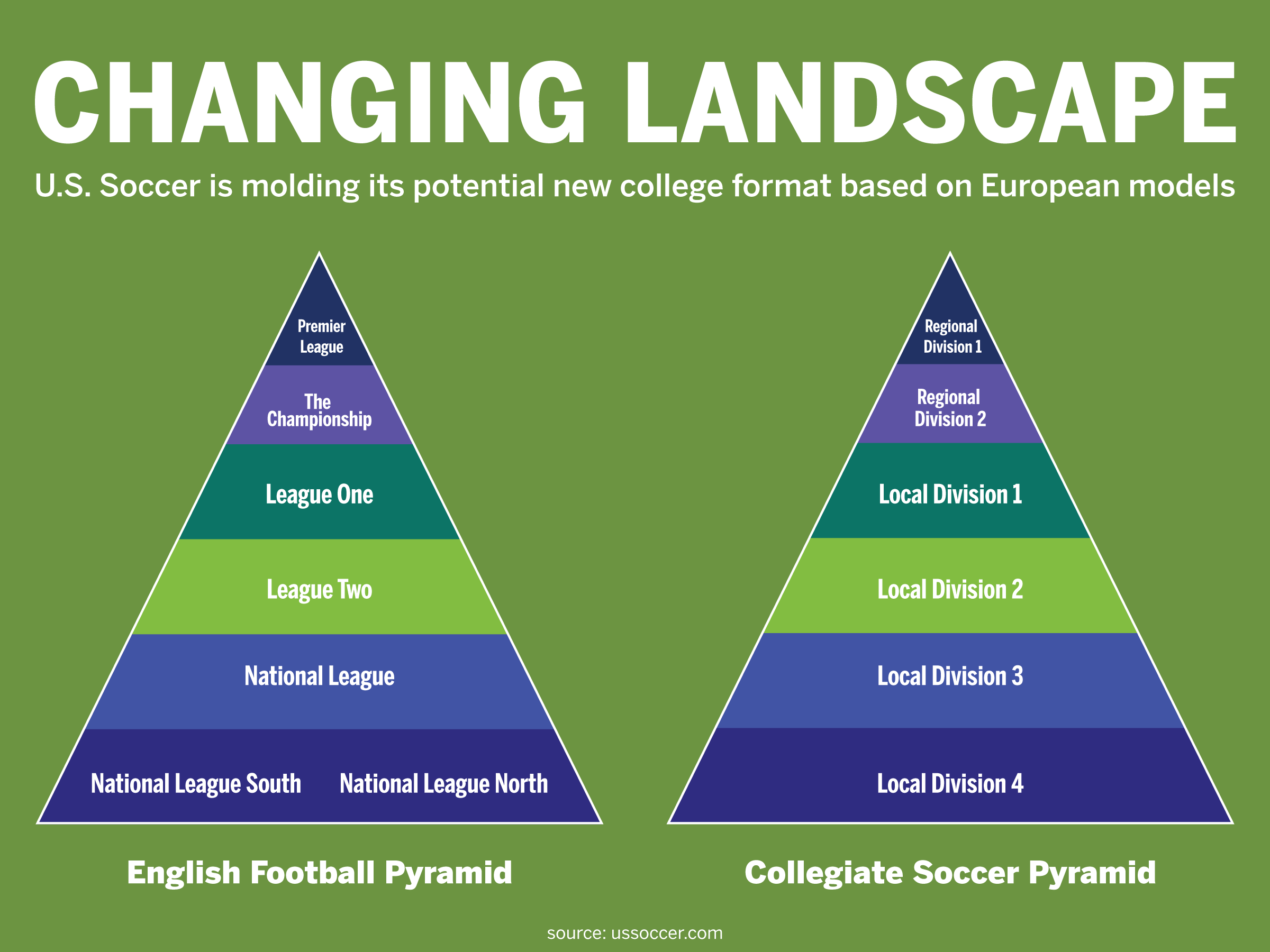

The proposed changes would replace the Power Four and other mid-major conferences with four regional “clusters” of 50 to 54 teams. The schedule will span six to seven non-concurrent months and culminate in a 64-team national tournament. The alteration would resemble European models, such as England’s six-tier football pyramid, by introducing season-by-season promotions and relegations for the first time in collegiate athletics history.

Without these alterations, the committee believes “college soccer risks dwindling relevance in the U.S. Soccer ecosystem.”

The Daily Orange spoke with Syracuse men’s soccer head coach Ian McIntyre, who led the team to a national title in 2022, about whether the change would be helpful for college soccer.

“There are lots of pieces that need to move in the right direction for it to fall into place. Big picture, our college soccer landscape and our game need to grow and evolve,” McIntyre said. “A full-year season makes a lot of sense. Regionalization from a financial perspective is common sense as well.”

What is a “football pyramid?”

In 1888, 12 English clubs formed the Football League — the world’s oldest professional soccer league.

Today, the pyramid features six distinguished leagues, including the Premier League and over two dozen regional competitions. Any team can be promoted or relegated based on where it finishes in the table. Other nations such as Spain, France and Germany also have a promotion-relegation setup for both the men’s and women’s game.

U.S. Soccer mirrors the same premise with Major League Soccer as its top league and the United Soccer League (USL) Championship as its second-tier. The USL announced in April it’d become the first U.S. Soccer League to adopt promotion-relegation and would operate separately from MLS.

Meanwhile, college soccer is an amateur league in the pyramid. It competes in conference and nonconference play, where teams can push for a conference regular-season and tournament championship or a national title.

If college soccer shifts into a promotion-relegation structure, it would be its first attempt to professionalize the game.

Sophia Burke | Digital Design Director

“It’s nice that our governing soccer body is looking to be invested physically, financially and emotionally in the development of our college game,” McIntyre said.

How does it differ from “Big 4” American sports?

None of the four major U.S. sports leagues — the NBA, NFL, MLB or NHL — operate in a pyramid structure.

The NBA’s G League, as well as MLB’s and the NHL’s minor leagues, allow players to get more game time before playing professionally. As a result, teams are more inclined to “tank.”

MLS also bases its draft picks on league performance, but its top overall picks rarely have the same impact as those in the NBA or NFL. Only two have won MLS Rookie of the Year and none have won the Landon Donovan MVP Award.

“As MLS looks at the FIFA model and the FIFA schedule, we’d have to align more with Major League Soccer, the (MLS) draft and the professional pathway,” McIntyre said.

While tanking isn’t an option in college sports, the 2025 college football season has seen nine Power Four head coaches fired within the first two months due to poor performance. It’s the third time in five years that at least six coaches have been fired before November, heightened by the House v. NCAA settlement approval.

Meanwhile, no Power Four men’s soccer head coaches were replaced entering the 2025 season. However, this new format, where poor performance leads to relegation, could lead to increased coaching pressure and higher-quality players in college.

Why does college soccer want to implement a promotion-relegation structure now?

FIFA, the World Cup’s governing body, expects six billion people worldwide to watch the newly expanded 48-team competition and over five million fans to attend the 104 matches in person.

Even with President Donald Trump’s travel ban and persistence to move games away from cities he deems “even a little bit dangerous,” the 2026 World Cup is expected to generate $30.5 billion in gross output, according to a FIFA-World Trade Organization (WTO) study in March.

“We believe strongly that these changes will have the greatest impact if implementation begins with the start of the 2026-2027 academic year, providing tangible financial benefit and taking full advantage of the American soccer momentum expected immediately following the 2026 World Cup,” NextGen College Soccer Committee wrote in its paper.

The primary concern for U.S. Soccer and the NextGen College Soccer Committee is the lack of college representation on the U.S. national teams, particularly the men’s squad. Just three former college players started for the USMNT during the 2022 World Cup.

To fix that, U.S. Soccer wants to limit players over the age of 23 from participating in college soccer, since it considers ages 17 to 23 a period where “college soccer can facilitate player development.” It also encouraged greater international participation and advocated for a “second chance pathway,” which would allow a player whose professional career had “stalled” to enroll and compete in college.

McIntyre believes an “enhanced relationship” between college and professional soccer could be beneficial, as men’s college soccer has become second fiddle to MLS and European club academies in producing top talent for the USMNT.

“The best players aren’t going to college,” McIntyre said.

How would it work?

In college soccer’s proposed new format, the regular season would begin in September and end in late April with a two-month break in December and January to “allow students to focus on exams.”

Teams would play one match per week, usually on Friday, Saturday or Sunday. Every school would play a divisional opponent twice — home and away — and a few “crossover games” against teams in their cluster. Each region would comprise two nine-team divisions of the “most competitive” teams in each geographic area. The second tier would feature four “local” leagues with eight to 10 teams.

McIntyre said the only caveat with the new format is that Syracuse wouldn’t be in the Atlantic Coast Conference, which he takes “tremendous pride” in representing.

After a play-in round, the 64-team national tournament would run from mid-April to early May and feature 16 teams per geographic cluster. Qualification would be based on where a team places in its division or league.

Once a national champion is crowned, each tier in the cluster would be re-determined “through on-field performance similar to promotion/relegation.” The committee also said an in-season cup is possible and didn’t mention if these changes would affect Division II and Division III schools.

The women’s collegiate soccer 2026 season would remain the same, besides starting in July rather than August and a potential spring 2027 competition for “certain elite programs.” It’s unclear whether women’s soccer will follow the men’s model after this upcoming year, with women’s college soccer serving as the “primary source of talent” for the four-time World Cup winning USWNT.

“The college landscape will change a lot for all sports. If you’ve got a governing body that is invested in the development of the college game, I think that’s good and could potentially be some kind of master plan that could help other Olympic sports as well,” McIntyre said.