T

he Cincinnati Bengals’ 2007 receiving corps was nearly impossible to defend. On one side, there was All-Pro Chad Johnson, better known as “Ochocinco.” On the other side was T.J. Houshmandzadeh, a seventh-year receiver fresh off a 1,000-yard receiving season.

Before the star duo ripped through opponents in the regular season, it was first tested by its teammates. First-round picks Johnathan Joseph and Leon Hall played the bulk of the reps at cornerback. Then there was Fran Brown.

The undrafted free agent out of Western Carolina began training camp in the back of the line, matching up with the undrafted wide receivers. Brown, however, knew if he wanted to make it in the NFL, he’d have to match up with the best.

“By the end of camp, he would be stepping up and trying to compete with (Johnson and Houshmandzadeh) every chance he got,” said Louie Cioffi, then the Bengals assistant defensive backs coach.

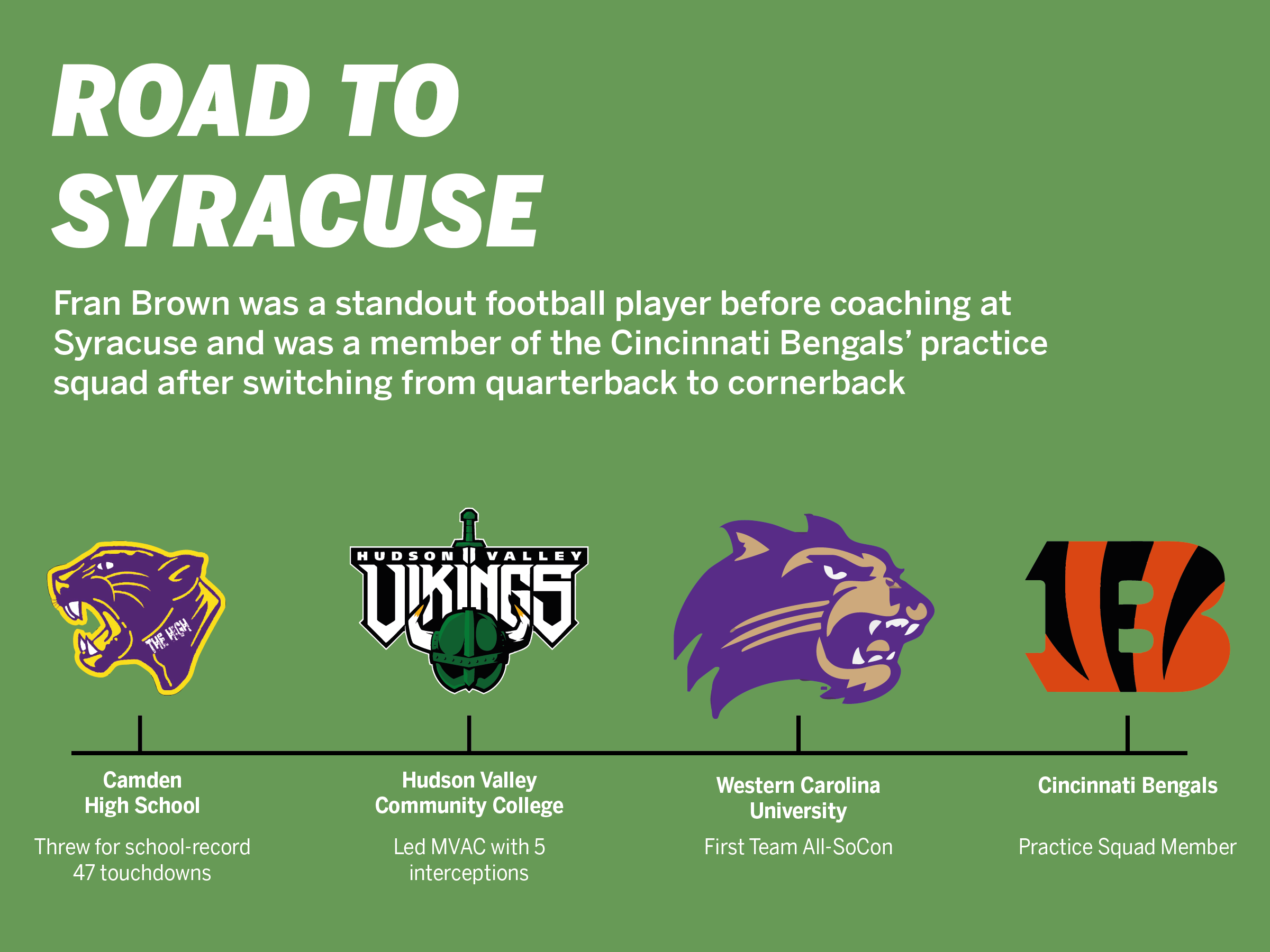

Over his first two seasons as Syracuse’s head coach, Brown often uses his playing career in a negative light as a joke to calm down his quarterbacks when they’re struggling. But what was Brown actually like as a player?

He earned First Team All-SoCon honors at Western Carolina before a short stint on the Bengals practice squad from 2007-08. The Daily Orange spoke with multiple of Brown’s coaches and teammates to detail his playing career before hitting the sidelines and leading the Orange into a new era as their head coach.

“There are certain people that command respect, and it doesn’t matter where they stand on the depth chart, or even if they’re on the team yet,” said Chuck Bresnahan, Cincinnati’s defensive coordinator from 2005-07. “This is a guy that came in, and guys noticed him. Fran was somebody who stood out.”

Brown’s desire to face Johnson and Houshmandzadeh nearly became an issue for Cincinnati’s coaching staff. Bresnahan said he had discussions with Cioffi and defensive backs coach Kevin Coyle about needing the starting cornerbacks to still match up with the starting wide receivers.

But far before scratching the NFL’s surface, Brown grew his football status throughout his childhood in Camden, New Jersey.

Ilyan Sarech | Design Editor

Brown showed the traits of a defensive back as young as 8 years old, according to Coach Muhammad of the Centerville Simbas. As the coach of the 105-pound weight class, Muhammad was first alerted of Brown’s talents through Norman Williams, his first coach. Williams, also known as “Coach Drip,” told Muhammad to wait until he saw Brown.

Like most youth programs, the best athlete starred at quarterback. Brown did the same. Once he moved up a weight class, Muhammad saw Brown study film and change plays at the line of scrimmage. He evolved into a “seasoned veteran,” knowing the finer details of the game and recognizing where each player should be on the field.

“Maybe every 10, 15, 20 years, sometimes more than that, you get one of those special athletes to come along,” Muhammad said. “(Brown) was one of them kids.”

While filled with talent, Brown has been the underdog his whole life. He explained his feelings before SU’s win over Clemson this season, while citing the lyrics of “Hate It Or Love It” by The Game and 50 Cent — “Hate It or Love It, the underdog’s on top,” 50 Cent famously says.

Brown’s on-field persona in college reminded then-Western Carolina defensive coordinator Geoff Collins of then-star NFL safeties Ed Reed and Brian Dawkins. Muhammad said, despite his intensity, Brown is an “old soul” and “easy to love.” But what stuck out most, even back then, was his genuine tone. Brown’s directness can be a lot to handle for some, said Mark Pease, one of his head coaches at Camden High School. However, it’s who he’s always been.

“He doesn’t put on a front for anybody,” Collins said. “He is Fran Brown 24 hours a day.”

By the time Brown reached high school, he stayed at quarterback and became fearless in the eyes of his head coach, Reggie Lawrence. Lawrence described Brown as “average-sized or smaller,” but a competitor.

Pease took over during Brown’s ascent, and the Panthers ran a West Coast offense. Brown made all the necessary throws and could expose defenses with his legs, Pease noted. He added that players from the New Jersey area wanted to transfer to Camden to play with Brown.

Brown rose to stardom on multiple occasions, taking down Overbrook as a sophomore despite trailing by 20-plus points in the fourth quarter. Then came the Thanksgiving matchup with crosstown rival Woodrow Wilson — now known as Eastside — where Brown led a triple overtime win.

When his prep career was over, Brown set the school record with 47 touchdown passes, while also spending some time at defensive back. The spotlight was never too bright.

“Playing in Camden is a tough place for youngsters to play, because it’s a very demanding city when it comes to athletics,” Pease said. “There’s a lot of high expectations, and they’ll let you know if you’re not playing well. And Fran, even if he had a bad game, was able to handle that pressure.”

Fran Brown poses for a photo with his former high school coach Mark Pease at one of Syracuse’s games. Brown mostly served as Camden’s quarterback, where he often made plays with his legs. Courtesy of Mark Pease

Once Brown’s playing career at Camden ended, he faced a setback. The quarterback wasn’t graduating from high school with his class. To receive his diploma, he needed to transfer to Woodrow Wilson and stay in school for one more year. Pease said Brown was ridiculed for the move from a social status perspective.

The switch allowed Brown to focus on his academics with fewer outside distractions. While he missed out on a college season in the immediate, he turned a negative into a positive.

“He wasn’t a big fan of being in school, but he knew that school played an important part in his ability to play football,” Pease said. “It took hitting rock bottom before Fran learned to put education as a priority.”

After graduating from high school, Brown finally earned his chance to shine at the college level. First, he took the road less traveled and went to Hudson Valley Community College, where he made the move to defense full-time.

SU quality control coach and recruiting staffer Emmanuel Marc now knows when he’s talking to his boss versus his “boy.” He, quite literally, lived the JUCO grind with Brown. The two roomed together as they chased their dreams of bigger and better opportunities.

Marc remembers Brown living the sport every moment of the day. He went to classes with a football in his backpack. Late at night, Brown challenged Marc to push-up contests to outwork the other players sleeping. Brown held the football in his arms as he went to bed. On days when the offense — Marc’s unit as a running back — beat the defense in practice, Brown wanted to play tackle football versus Marc outside the dorms.

The duo knew it was taking a chance on itself to earn college offers. Marc said Brown locked in on his education and earned his associate’s degree in just one year. They also matured in Marc’s eyes, learning how to “become a man” by paying bills and arranging their meals, which often ranged from peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to noodles.

In games, Marc remembers Brown talking to the opposing coaches during the quarterback’s cadence, daring them to throw his way. He excelled once again and earned a coveted Division I opportunity.

Former Western Carolina defensive coordinator Geoff Collins takes a photo with Fran Brown after a game. In his time with the Catamounts, Brown finished with 93 tackles, five interceptions and 16 pass deflections. Courtesy of Geoff Collins

Then-Western Carolina linebackers coach Matt Rhule first found Brown and recruited him. Once Brown joined the squad, he made his goals clear. Former head coach Kent Briggs recalls Brown telling him he wanted a career that could support his family. Brown and his wife, Teara, welcomed their first son, Fran Jr., in 2004. Collins said he babysat the now-SU long snapper multiple times. At the same time, Brown was emerging as a team captain.

Collins remembers Brown starting almost every game except one, when the cornerback injured himself playing pickup basketball during a bye week. The mishap earned him the nickname “hot sauce,” as Collins joked Brown thought he was “hot sauce” playing basketball instead of football. The coach still has the moniker saved as Brown’s contact in his phone.

But when Brown was on the gridiron, he was the perfect chess piece in Collins’ operation. Western Carolina has won just 17 of its 78 rivalry matchups against Appalachian State. The Battles for the Old Mountain Jug swung in the Catamounts’ favor only once from 1999-2013. That was in 2004, and it was partially thanks to Brown.

The Mountaineers’ offense was flying high, as future Appalachian State Hall of Famer DaVon Fowlkes soared to over 100 receptions and 1,600 receiving yards on the season. Knowing Fowlkes’ skillset, Collins needed an equalizer. Enter Brown.

“That kid I wasn’t going to worry about,” Collins said. “Because I knew Fran Brown was going to lock him down.”

Brown followed Fowlkes throughout the game and limited him to five receptions, half of his game average for the season. Collins built the rest of the defense around Brown, and despite Appalachian State’s efforts to move Fowlkes under center, the Catamounts won 30-27.

So, when Brown reached the NFL a few years later, matching up with talented wideouts like Johnson and Houshmandzadeh was nothing new.

Cioffi said Brown was near the top of the Bengals’ list once the draft ended and his name wasn’t called. Brown’s playmaking and enthusiasm stuck out. Cioffi recalls other undrafted defensive backs declining offers from Cincinnati due to its depth at the position. Brown bet on himself again.

What the Bengals saw on tape carried over to training camp. However, the business of professional football prevented Brown from sticking around.

In 2007, the NFL limited practice squads to eight players. After multiple Collective Bargaining Agreements, NFL teams now have 16 practice squad spots, with an additional spot for International Pathway Players. Bresnahan said the coaching staff twice wanted to sign Brown to the active roster but didn’t, taking wide receivers instead.

“If you go back and look at those rosters, we had a lot of really high draft picks invested in the position,” Cioffi said.

“He’s somebody that we would have signed without question. We just didn’t have that opportunity,” Bresnahan added.

When his NFL dreams turned sour, Brown had to make ends meet. But he couldn’t leave the game he’d known his whole life. He worked at a local hospital, a job Pease’s wife helped him land. Meanwhile, Brown stayed in game shape and trained young football players. He worked for Nexxt Level Sports in South Jersey and, through some connections, earned a spot as the defensive backs coach at Paul VI High School in Haddonfield, New Jersey.

The rest is history.

Fran Brown strolls across the field during Syracuse’s road clash with Miami. Brown led the Orange to a 10-3 debut season before a 3-7 campaign thus far in 2025. Joe Zhao | Senior Staff Photographer

Through his playing career, Brown built connections as he worked his way up the coaching ladder. He worked small roles on Temple’s staff but earned the defensive backs job when Rhule took over as the head coach. When Rhule moved to Baylor, so did he.

Following a few more moves through the Big Ten and SEC, Brown took over at Syracuse and reconnected with his past. He hired Marc to join the recruiting staff. In Brown’s second season, he brought in Coyle as a senior defensive analyst before he moved to UCLA midseason. Pease’s son, Mason, is an assistant on the equipment staff.

Pease credits SU’s quad walk and pregame suit-wearing to what Brown experienced at Camden High. As the world was shocked at Brown putting his team through sprints following a win over UConn, Muhammad knew he had gained the idea from his time playing for the Simbas in his youth. Brown often went through a drill called “poles of pride,” where the team jogged to the 50-yard line and sprinted back.

His playing career molded the philosophies Brown lives by as the leader of a Power Four program. The 43-year-old didn’t live out his initial dream of NFL stardom. But now, he’s in the spotlight, taking a redirected path to get there.

Collage by Ilana Zahavy | Presentation Director, photos courtesy of Western Carolina Athletics, Cincinnati Bengals

Published on November 20, 2025 at 12:00 am