Old friends, white stones: Go Club continues 60-year legacy at Wegmans

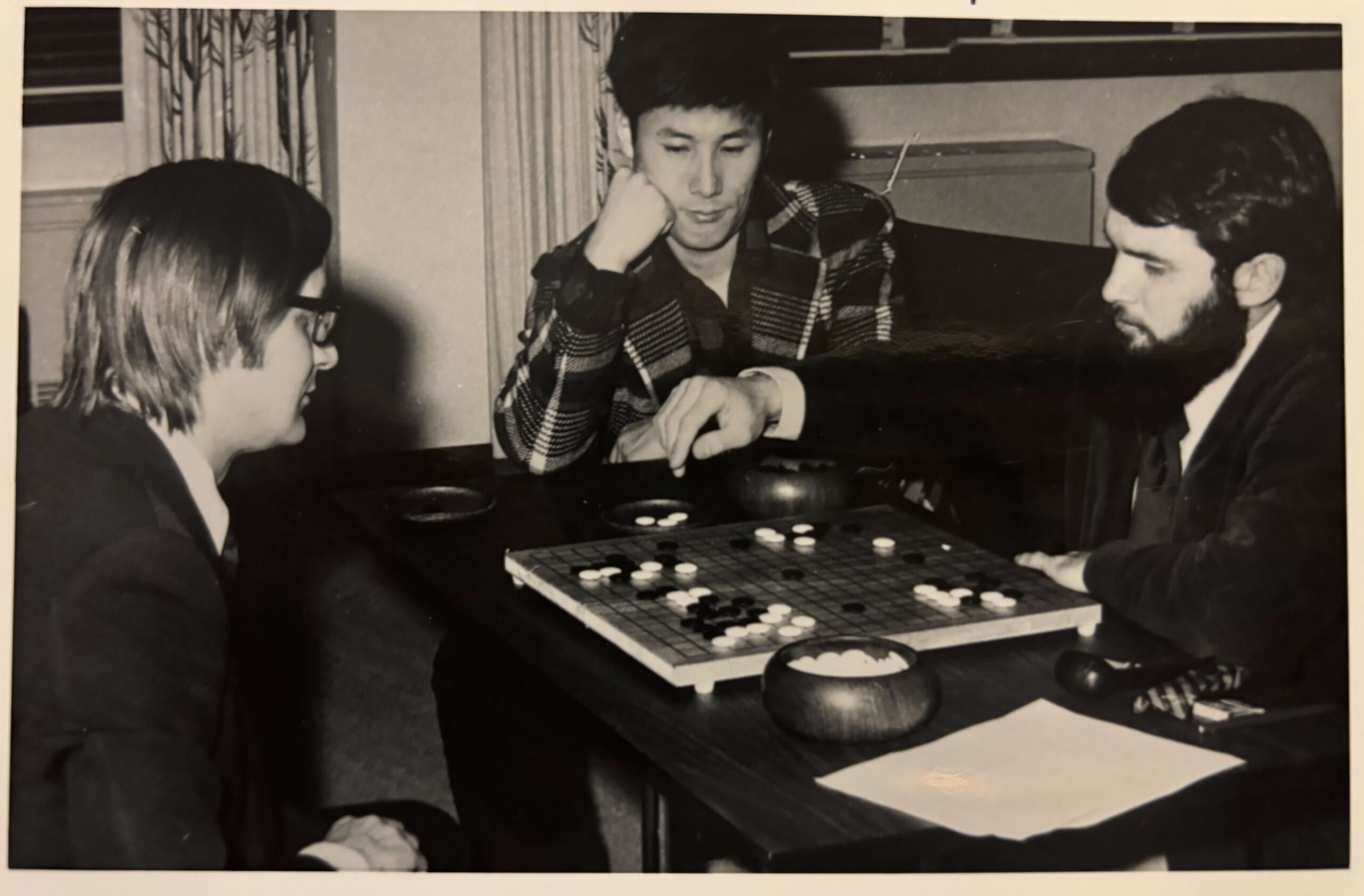

Mark Brown and a Syracuse Go Club member face each other in a game of Go at one of the club's meetings inside Wegmans Dewitt Café. Brown, a former Syracuse University professor, founded the club on SU's campus in 1967. Cam McGraw | Asst. Copy Editor

Support The Daily Orange this holiday season! The money raised between now and the end of the year will go directly toward aiding our students. Donate today.

Past the freezers, produce aisles and customers, in the Wegmans DeWitt Café, sit a few old wooden boards with faded grid lines and small black and white stones stacked in bowls. The setup looks simple. But for the Syracuse Go Club, it’s nearly six decades of history.

“I looked in my attic and found a little booklet that had a lot of crazy games, and it gave a description of the game Go,” Mark Brown, a former Syracuse University philosophy professor, said. “I read about a page and said, ‘You can’t make a game out of that!’”

Brown founded an informal Syracuse Go Club in 1967 on SU’s campus after playing Go with other chemistry, engineering and computer science students and professors at various houses. The club still meets today, though they’ve found a more permanent location.

When he returned to SU after a year on leave in 1966, he learned the informal meetups had stopped, and decided to start the official club himself. Now the club is approaching its 50th anniversary.

The game Go is a two-player board game; each person takes turns placing black and white stones on a 19-by-19 grid. The goal is to surround more territory than your opponent by enclosing large spaces. Once placed, stones cannot move but can be captured by an opponent if surrounded. At the end of the game, captured stones and the total grid area are added up by each person to see who won.

The game Go was invented in China over 2,500 years ago, making it one of the world’s oldest board games. Although the rules are simple, the game was designed as a tool for strategy and discipline, and its influence and popularity eventually spread.

Brown started playing the game at SU but first discovered it as a kid.

The club quickly drew interest on campus with around a dozen members, including now SU alum Anton Ninno, who happened to be one of Brown’s former students.

Ninno said his interest in eastern philosophy sparked his curiosity about Go. Concepts of balance and discipline are core aspects of the region’s philosophy and deeply intertwined with the game of Go. Brown said he remembers trying to learn as much as he could about the game — even though there were very few books in English — before bringing it to his academic advisor.

“I pulled this book out and said, ‘Hey, I found this game, you might really like it,’” Ninno said. “He started laughing and said, ‘We have a Go club here,’ and I said, ‘Why didn’t you tell me?’ and he responded, ‘Well, you never asked.’”

That moment sparked a friendship that has lasted for more than 50 years.

As the club expanded, Brown said Ninno gradually started to take the reins. Ninno brought in professional Japanese players who would play 20 games at once.

Membership grew beyond the university after more advertising from Ninno. They chose Thursday night meetings because “people would be partying on Friday and studying on Wednesday,” Brown said.

Parking issues eventually pushed the group off campus, and after a brief stint at a Westwood Street coffee shop, Ninno moved the club to the Wegmans in Dewitt in December 2002. He credits his wife for the switch; she noticed people holding informal meetings at the grocery store.

The club’s first meeting at Wegmans was featured in The Post-Standard newspaper, which attracted more new players. But for longtime member Richard Moseson, joining the club took years.

Mark Brown and Anton Ninno play each other in a game of Go in 1974. Brown founded a club devoted to the game in 1967, the Syracuse Go Club. Courtesy of Anton Ninno

Moseson heard about the Go Club in 1996 through an email but could never track down where they were meeting. It wasn’t until Ninno moved the club to Wegmans that Moseson was able to join.

“We had some good players playing here in the early days,” Moseson said. “Or at least my early days.”

Brown eventually ended all campus meetups and fully transitioned gameplay to Wegmans. The group still occasionally got SU students to join for a year or two before graduating.

Alongside the game of Go, Ninno also organizes casual chess meetups on the opposite side of the Wegmans seating area. Boards are set out several hours before Go players arrive, and members begin to compete at each table.

Both Ninno and Brown say one of Go’s most meaningful features is its handicap system to balance skill levels between games. Unlike chess, where there are multiple pieces with different values, Go’s identical stones can easily be subtracted, allowing experienced and newer players to compete fairly by adjusting the score at the end.

Brown said he appreciates the evolution of his friendship with Ninno from student-adviser to opponent.

“Oh yeah, I hate his guts,” Brown said. “We usually ignore each other at the grocery store.”

Despite the banter, their friendship is tight, Brown said. Brown calls Ninno the “muscle” of the group, citing his advertising and recruitment of new players. Ninno used to mail letters to student organizations, but he said most players preferred to play casually with friends rather than join a formal club.

Ninno said he is surprised that Go is not as widespread as he expected, especially in the past when there was no internet or video games. Still, he continues doing presentations at nearby colleges and placing boards in libraries to spark curiosity for students.

Brown jokes that his age and memory are catching up to him, but still, he and Ninno have logged more wins than anyone else in the club.

“Well, some of my oldest friends are Go players,” Brown said. “And boy, they’re getting old.”

Now, nearly 60 years after its inception, having undergone location changes and shifting generations of members, the group still gathers each week, facing the same opponents they’ve known for decades.

“White stones never die,” Ninno said.