Opinion: Support human writing, demand artificial intelligence copyright laws

LLMs that rely on human work to train their algorithms are unethical, our columnist writes. She argues we should seek out human-generated content to support authors in a competitive market. Emma Soto | Contributing Illustrator

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Support The Daily Orange this holiday season! The money raised between now and the end of the year will go directly toward aiding our students. Donate today.

A copyright war is waging between authors, other content creators and artificial intelligence companies. While AI users are enjoying the new shortcuts of AI-generated writing, or the summarizing of other written works, the original authors are not thrilled. Sixty-five lawsuits have been filed as of Dec. 5, with few settled.

After learning AI companies scrape books and other written works for data to train their models, I was shocked this use doesn’t violate copyright laws. Even if it is legal to use AI this way, I would never use it for assistance with my own writing or seek out books created by code.

But the courts don’t seem to agree with me. Training large language models with original works like books and articles currently qualifies as fair use under copyright law.

Nina Brown, an associate professor at Newhouse, researches and writes about AI’s ever-evolving legal landscape. When looking at these cases broadly, Brown said there are a few claims worth paying attention to, mainly involving the input and output of content from AI companies.

The precedent has been set by Bartz v. Anthropic and Kadrey v. Meta Platforms, Inc. that AI companies are allowed to scrape books to train their LLMs. In court, this act of training was put through fair use’s four-part test and prevailed. The first part of the test addresses the “purpose and character” of the use, and asks if the defendant’s content is transformative or not.

Since the writing resulting from these LLMs is quite different – or by Brown’s legal terminology, “spectacularly transformative” – from the original texts they were trained on, AI companies are allowed to scrape. But the output content is where things get tricky.

“The last factor (of the fair use test) is the most important, and that’s market harm,” Brown said. “Bartz sort of concluded there’s no market harm. They’re not creating substitutes for the original, which is the big concern there.”

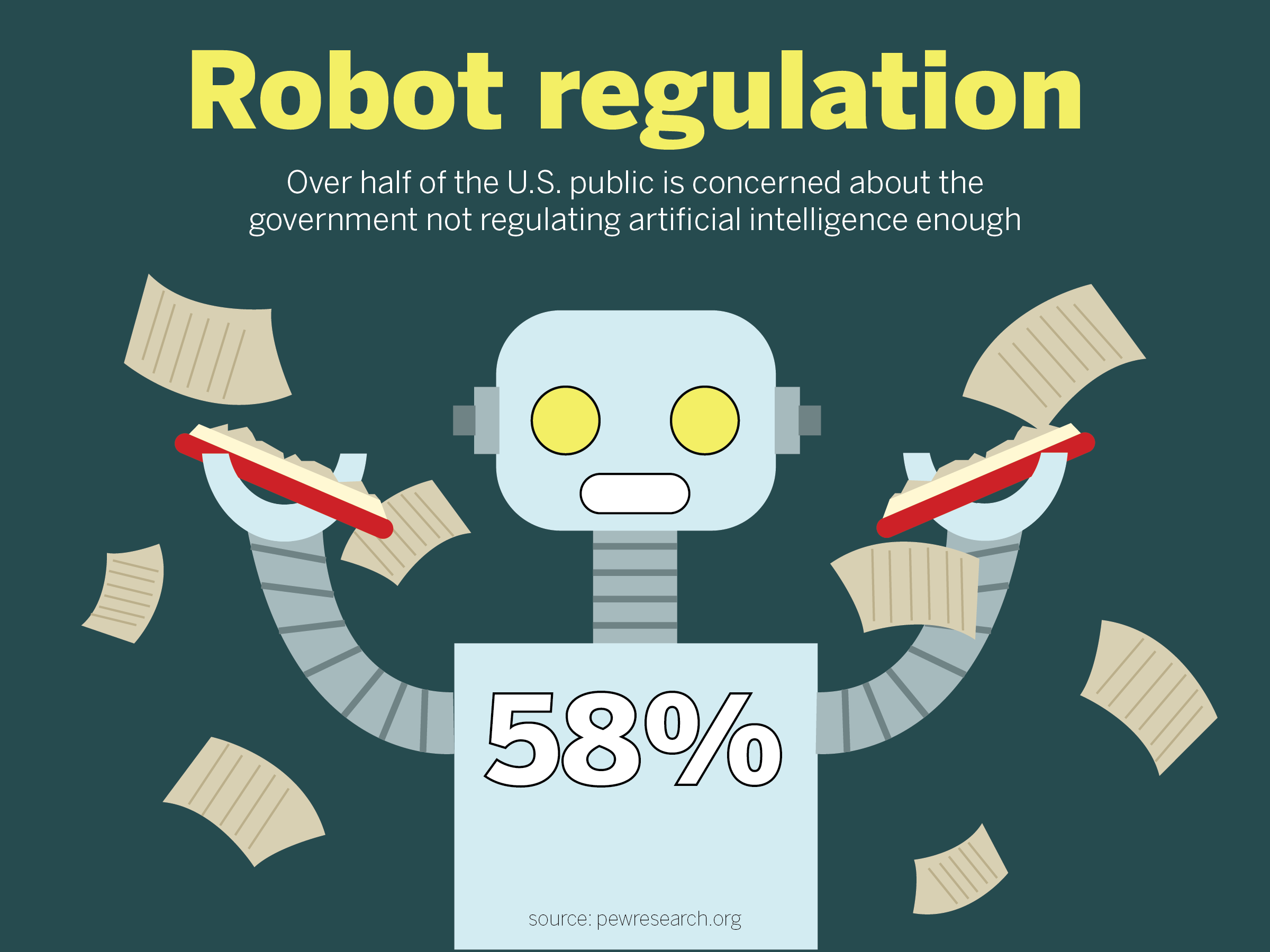

Instead of creating market harm, these AI-created or AI-assisted works would create competition between human and machine authors.

Zoey Grimes | Design Editor

But market harm can occur if the output causes an audience to bypass the original content, causing the original author to lose profits. Authors could make this argument if potential readers use AI to summarize books instead of buying them.

The Authors Guild, a professional organization for writers, has also filed a lawsuit against OpenAI in regards to copyright infringement and the monetary harm to authors. The organization calls attention to the fact that many authors are already underpaid, and using their work to train AI systems without compensation doesn’t help.

Brown considers the Guild’s argument to be more of a human plea than a legal one, and I agree. But, these lawsuits will continue. AI companies will have enough resources and funding to fight in court for years. With this in mind, the problem shifts from legality to ethicality.

The responsibility needs to fall on the consumer. Taking the extra step to confirm your reading content without AI intervention is important.

Whether it’s a book, article or short story, I read in hopes of gaining experience or knowledge from a new perspective. I detest the idea of reading any content produced by or in collaboration with a computer system. Even if I did read this content, it would not compare to human-written works.

AI’s capabilities are limited to what it has been trained on; a coded program tasked to write is incapable of understanding the human experience. An algorithm could never write Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” since code has never lived to tell the tales of the intersection of sexism and racism. Or begin to replicate Robin Waller Kimmerer’s “Braiding Sweetgrass,” which taught me about indigenous wisdom and connection to the environment.

In a society where bingeing millions of 15-second TikTok videos has become normalized, it is vital to find human-written works that hold our attention and impart knowledge.

Authors must continue to call on publishers to refrain from using AI to protect their craft as well. An open letter to publishers from over 70 authors cites problems with AI “authors,” cover art or audio book readings. We shouldn’t normalize digesting such content, even if it is legal to produce.

If you want to support human authors in their fight to keep books human, click here to sign their open letter.

Bella Tabak is a senior majoring in magazine journalism. She can be reached at batabak@syr.edu.