N

estled on the outskirts of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in Nedrow, New York, off Interstate 81 South’s Exit 78 is a quaint diner called Firekeepers, where 95-year-old Oren Lyons spends almost every morning eating breakfast and engaging in daunting philosophical discussions.

On this particular morning, he orders two eggs sunny side up, a heaping pile of bacon — per special request — one pancake and half an order of home fries with onions: a meal fit for a king. Oren is treated like one here, too. He owns the place. Firekeepers employees light up like beams when they see his white Subaru pull into the parking lot. Patrons shake his hand, showing gratitude for his work as a Faithkeeper of the Haudenosaunee’s Wolf Clan.

The restaurant offers Oren a refuge from the troubling trends he sees in contemporary society and the chance to spread wisdom to those who’ll listen.

Haudenosaunee values center around peace and humans’ spiritual connection to the Earth. Yet Oren watches the natural world drifting further away from how his ancestors intended it to be. He sees greed. Inequity. War. Natural disasters. Famine. Everything except peace.

He believes time is running out for mankind to fix the mess they’ve inherited from themselves.

“You look at what’s going on today, with two wars raging overseas and how fast the environment has deteriorated, we’re in big trouble,” Oren said before scooping the last few bites of bacon with his fork. “I estimate on my own personal estimation, it’s not scientific by any means, I would say that 2034 is the point of no return. We need to do something before then.

“But it’s not over. The whole point is that it’s not over.”

Oren’s cynical forecast doesn’t represent what’s inside his heart. For those within the Indigenous community, he’s the de facto peacekeeper and vessel of knowledge for how the world can learn from the Haudenosaunee to solve its long-standing problems. His trailblazing journey — one of Syracuse University’s first Indigenous students, a Faithkeeper for over five decades and the originator of the Haudenosaunee Nationals lacrosse organization, among other achievements — makes him a beacon of influence for Indigenous rights.

On Friday, Sept. 12, Oren and former SU men’s lacrosse head coach Roy Simmons Jr. will receive the Alfie Jacques Ambassador Award, an honor named after the late stickmaker. It recognizes others’ contributions in preserving lacrosse’s native origins; the Haudenosaunee created lacrosse around 1100 A.D. to give thanks to The Creator.

The distinction encapsulates Oren’s tireless effort to create equality between Indigenous folks and the governments they reside in and often suffer oppression from.

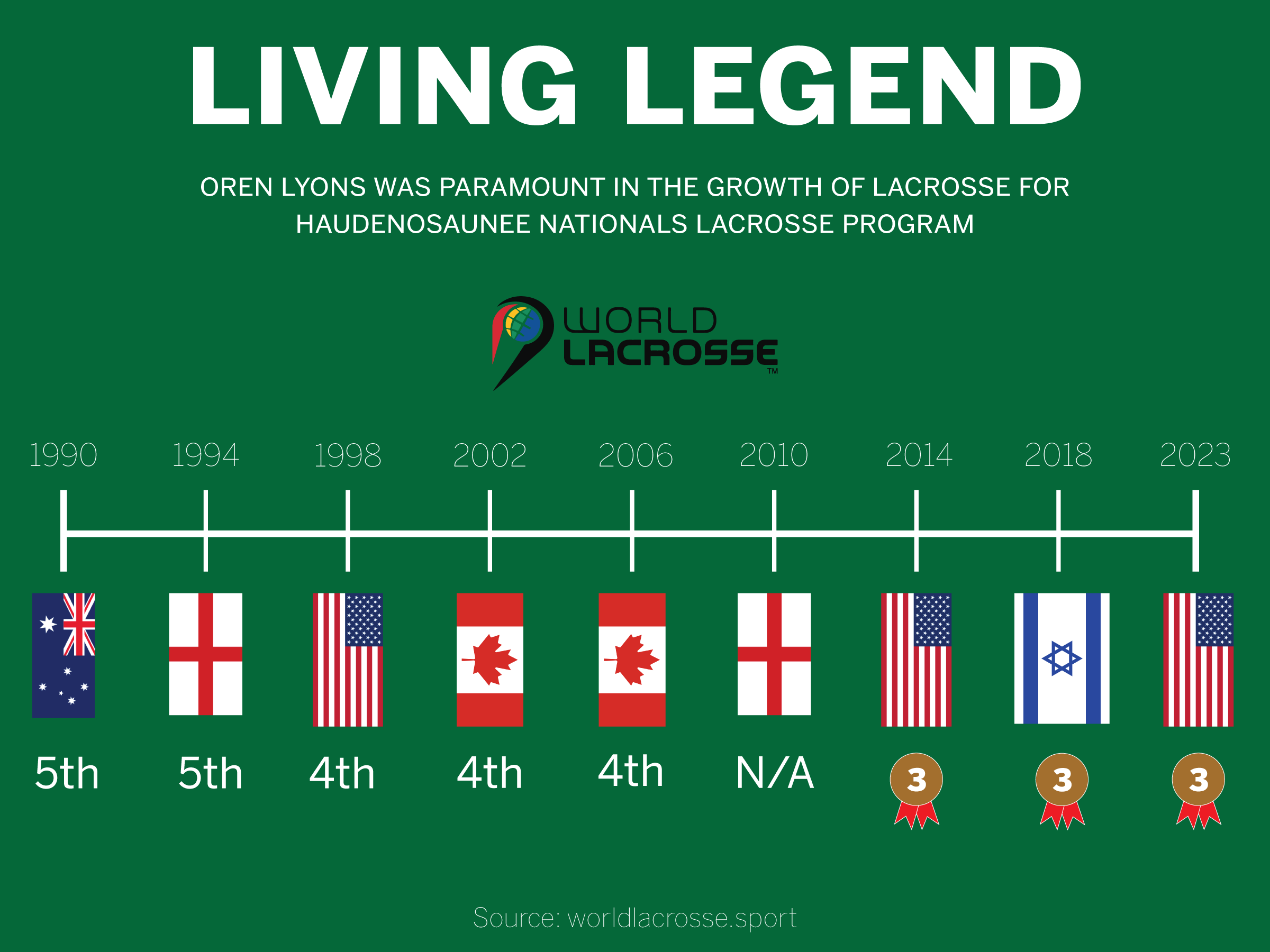

Katie Crews | Design Editor

Despite thinking the world is slowly slipping away, Oren is always calm. He feels this way, in part, because of the constant roadblocks he’s faced when advocating for his people’s sovereign expression.

He’s been called derogatory names like “forest dweller” when speaking on the floor of the United Nations to educate member countries about Indigenous history. He’s been laughed at when pushing for Haudenosaunee — an Indigenous group whose territory extends throughout parts of central New York, Ontario and Quebec — representation in global lacrosse competitions under their own flag, even though it’s their sport. He’s been told by members of the Russian Federation that it’s “indigestible” for Indigenous people to be considered equals in society.

As the weight of the planet bears down on him, why does Oren keep going?

He wants to leave this Earth knowing he did all he could to preserve Haudenosaunee values — pillars Oren believes can heal the world from strife.

“His vision is extraordinary. He can see things that other people struggle to understand,” said Betty Lyons, Oren’s niece through marriage and a member of the Haudenosaunee External Relations Committee. “People think that they know the depth of his mind, the depth of his soul; they think that they know him but they have no idea. He’s probably one of the strongest leaders we’ve ever had.”

• • •

Oren tied a white handkerchief to his right knee — informing his fellow soldiers that this was his final jump. The year was 1950. Oren, a 20-year-old, was drafted for the Korean War as a paratrooper in the United States Army’s 82nd Airborne Division, an elite group of specialized soldiers. Oren became a paratrooper because of the salary. Soldiers who jumped out of planes for a living earned more — they call it “jump pay.”

Yet, after about a half-year on the job, Oren’s last plane ride proved to be his most expensive leap of faith.

Oren led the assignment. He held supreme experience among a plane filled with new recruits. Usually, on one’s final airborne mission — per Rex Lyons, Oren’s son — you pay somebody else to take their dog tags, avoiding having to actually complete the final jump. But Oren was stubborn.

“He would never pay somebody else to do that,” Rex said.

Oren overlooked the mission destination — which remains top secret — daydreaming about the reward one last payday would bring him. In the 82nd Airborne, you’re trained not to be a sitting duck. Soldiers need precise timing to end up in their desired landing zone. But Oren ignored his training this time. All of a sudden, he heard the pilot screaming at him, imploring him to abort the mission since he’d missed his jump.

I’m not going all the way back down to be forced to re-do the jump.

Panicked, Oren stumbled onto the floor and plummeted out of the aircraft’s rear hatch. Paratroopers are instructed to pull their parachute after counting to “three one-thousand.” Oren’s count was at five one-thousand, and as he rapidly flailed through the sky, he couldn’t grab his parachute. The number 2,000 popped into his head. At that number of feet, the Army says you’re as good as a hole in the ground if you haven’t yet pulled your parachute. Oren approached the point of no return. Then he crossed it.

He scrambled to grasp his final lifeline and, hundreds of feet before reaching a thick patch of trees, miraculously released the parachute. Oren’s speed, though still blazing, decreased enough to lessen the ensuing impact — he collided into the top of a massive tree, getting his opened parachute stuck in the branches. Oren hung there hopeless, but alive.

He had to get down somehow. His backpack contained a button that’d propel him out of his positioning, though risking a fall akin to a death wish. Oren smashed the eject and crashed into the ground. Both of his shins were broken, but he was alive. His battalion laughed at him, but he was alive. He spent the next six months in the infirmary, but he was alive.

During his half-year recovery, Oren had one regret while lying in the hospital bed: His battalion got thrust into a highly confidential mission, and he wished that could’ve been his final task for the Army.

Oren eventually found out his troop’s mission was to assist the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission’s first testing of nuclear weapons at its Nevada Test Site on Jan. 27, 1951. Every single soldier who went to the test had their lives cut short, slowly dying from nuclear radiation poisoning. Oren is the only one from his battalion who remains alive.

Oren Lyons poses wearing traditional Haudenosaunee clothing. Lyons is the Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation, striving to fight for equal rights for Indigenous people. Courtesy of Rex Lyons

A main principle of Haudenosaunee culture is that everything happens for a reason. If you don’t believe in fate, Oren will remind you about his tightrope walk over the gates of heaven. He believes it was the universe’s way of leading him to a life of servitude for his people. It’s the experience that stamped his spiritual connection with the natural world.

“People get a little skeptical about people having a purpose,” Rex said. “We know it’s real. There are things in place where you have a mission and you have a journey ahead of you that’s pre-destined.”

• • •

At Firekeepers, Oren arrived donning a grey Jordan Brand Haudenosaunee Nationals tracksuit with a white “Jumpman” logo above his right breast, a yellow hawk on the left side of his jacket and a purple hat featuring another yellow hawk, the Haudenosaunee’s staple lacrosse logo.

While waiting for his meal, a man walked up to Oren and Rex. The three exchanged pleasantries, then talked about lacrosse. The man asked the two about how the Haudenosaunee Men’s U20 Nationals Team did in the 2025 World Championships. Rex — a prominent Haudenosaunee Nationals board member — informed the table it finished fourth after a 15-14 loss to Australia. The man was disappointed, but Oren cracked a smile.

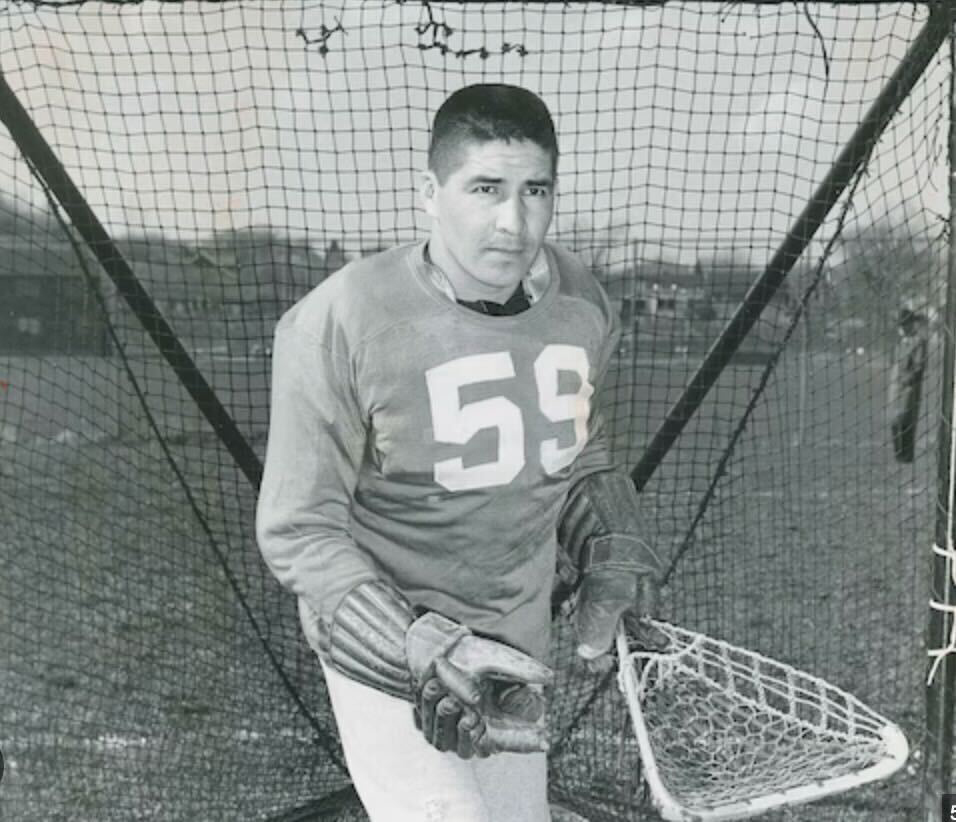

“I was a goalkeeper for many years,” Oren began telling the man, reminiscing on his playing days. “Everybody else was always down on the other end (of the field).”

Win, lose or draw, Oren is proud of how far his lacrosse program has come. In 1983, Oren and his friend Rick Hill helped create the Haudenosaunee Nationals, originally the Iroquois Nationals. Their annual budget pales in comparison to USA Lacrosse’s $20 million — not cracking a million — yet are still perennial World Lacrosse Championship contenders.

Oren’s impact on lacrosse, the Haudenosaunee’s sacred “medicine game,” reflects his commitment to protecting Indigenous rights. He used his lacrosse-based platform to launch his career as an activist for the Haudenosaunee people, extending his influence across multiple generations.

Oren Lyons played goalie and donned a No. 59 jersey for the Syracuse men’s lacrosse program during his time at the university. Lyons helped SU to an undefeated season in 1957. Courtesy of Robert Carpenter

“In spirit, he’ll one day sit on our shoulders and whisper to us, and we’ll call it instincts. Because our ancestors are speaking through him. And someday he’ll speak through our children,” said former All-World Team Haudenosaunee lacrosse player Neal Powless, now the head of SU’s Ombuds Office and close friend of Oren.

The road that shaped his love for his heritage began when he unexpectedly became the man of the house.

When Oren was 26, his father, Oren Lyons Sr., died at age 45. He was hit by a truck. Lyons Sr. was a box lacrosse star in his heyday and later served as a referee while Oren competed on the Onondaga Nation reservation. The accident left just Oren and his mother.

The two would take their wagon to the local market to buy everything they needed in bulk; from flour and salt pork to potatoes. Oren hunted the rest by himself. He killed deer, coyotes and any other animal that roamed for his family to eat.

In the meantime, he excelled playing lacrosse on the reservation. Soon, Oren would no longer be forced to put himself in peril to provide for his family.

In 1953, after recovering from the Korean War, then-SU head coach Roy Simmons Sr., father of Simmons Jr., approached Oren about playing lacrosse for the school whose grounds lie on the Haudenosaunee’s ancestral land. Oren accepted, earning a scholarship to play lacrosse and attend SU’s College of Fine Arts.

He was among the university’s first-ever Indigenous students.

By the time Oren graduated from SU in 1958, he’d made his imprint on the school. Alongside star goal scorer Jim Brown, Oren led the Orange to an undefeated national championship-winning season in 1957 as the starting goalie. Oren earned All-American honors in 1958, later being inducted into SU’s Athletic Hall of Fame. He also became the first person in his family to graduate college.

Oren played professional lacrosse for the New York Lacrosse Club (1959-65) and New Jersey Lacrosse Club (1966-70) before returning to the Onondaga Nation in 1970. Lacrosse, the same way it is for most children on the reservation, is Oren’s spiritual escape. It’s a game Oren prides himself on respecting. By playing lacrosse with high effort and intensity, Haudenosaunee people feel they’re providing peace to The Creator.

It’s Oren’s job to uphold those traditions.

Upon returning home, he was chosen to be a Faithkeeper of the Haudenosaunee’s Wolf Clan. For the Haudenosaunee, clans link families together from across the group’s Six Nations, meant to establish unity among tribes who were once at war. Oren remains the most influential living Faithkeeper, seen as the ultimate authority for peace and education.

“He’s become a person who you can call on to come and help with any particular situation in their community,” said Leo Nolan, a Haudenosaunee Nationals board member and close confidant of Oren. “He’s helped call out the misunderstandings and some of the tension that goes on to try and keep us safe and be an optimistic voice to all.”

As a Faithkeeper, Oren is often tasked with talking to leaders of foreign nations. He attends U.N. meetings and has solo discussions with politicians to advocate for the Haudenosaunee’s recognition as a sovereign group of people. The goal is for their independence to be honored through both the international acceptance of Haudenosaunee passports and ability to participate in global lacrosse tournaments, among all the freedoms that fall under the blanket of human rights.

Over half a century, he has slowly but surely increased Indigenous representation.

The Haudenosaunee were initially denied from the 1986 World Lacrosse Championships in Canada by the Federation of International Lacrosse, but they are now allowed to compete in nearly every global competition — though their 2028 Olympic qualification status is uncertain.

Haudenosaunee people can travel freely with the Nation’s passport to most U.N. member nations. Most Haudenosaunee citizens opt not to register for U.S. passports.

The Haudenosaunee are also the largest self-governed Indigenous group left on U.S. soil.

Robert Carpenter, the founder of Inside Lacrosse and a historian of the sport, said it was a painstaking process for the Haudenosaunee to receive these rights. It was even tougher for Oren to deal with the bureaucratic red tape that often prevented him from educating major nations on the Haudenosaunee’s sovereignty.

“He had to convince people within his own community, and he had to convince people in the larger lacrosse community that this team deserved to be there,” Carpenter said.

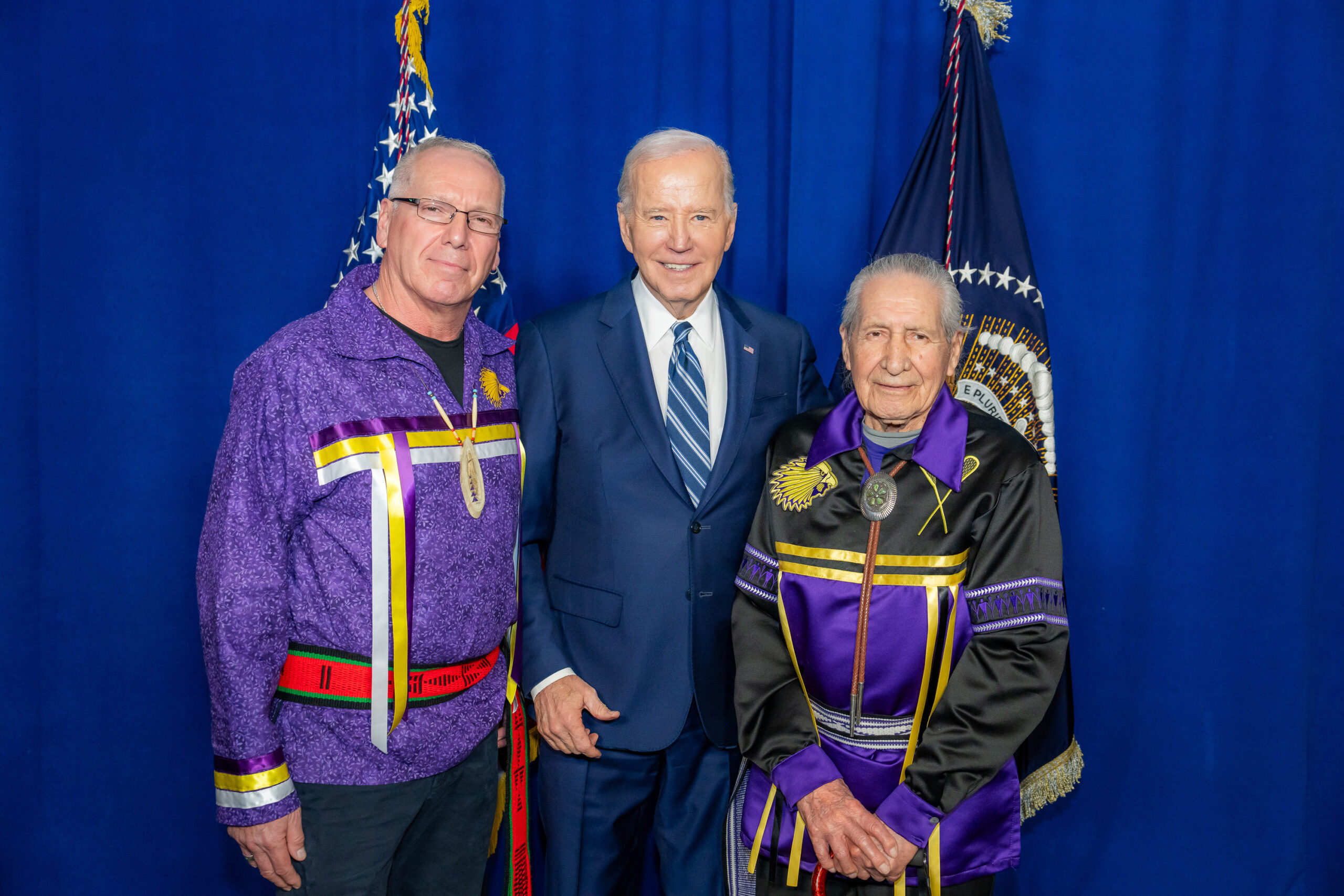

Though times have changed. Two years ago, Oren, Rex, Nolan and other Haudenosaunee representatives traveled to the White House in Washington, D.C., to meet with 46th U.S. President Joe Biden and officials from nine other countries. They were there to inform them about their history creating lacrosse to advocate for the Haudenosaunee Nationals’ inclusion in the 2028 Summer Olympics.

The roadblock is simple: the Haudenosaunee Confederacy isn’t a country. But they believe they deserve a special exemption due to their innate contributions to lacrosse.

Oren and Rex Lyons pose alongside former President Joe Biden after a meeting at the White House in 2023. At the meeting, Oren advocated for Haudenosaunee representation in the 2028 Olympics. Courtesy of Rex Lyons

Inside the White House corridors in summer 2023, Oren got up to speak in front of the leaders. His speech was direct and earned encouragement from the parties involved, Rex and Leo said. The Haudenosaunee often prepare physical presentations to get their story across to outside nations, Nolan said, but they’ve found that having Oren front and center is the best tool to make progress.

“That really was a turning point for these countries from a diplomatic perspective,” Nolan said of the Haudenosaunee’s White House meeting. “I think they got the message that our status as a nation, a recognized sovereign nation, it’s important to consider (the Haudenosaunee) for future activities like this.”

On Dec. 6, 2023, Biden announced the U.S. is in full support of the Haudenosaunee’s inclusion to play lacrosse in the 2028 Olympics.

Though Oren is uneasy about the future that lies ahead dealing with Donald Trump — a president who’s pushed for unfavorable policy toward Indigenous people — he’s never been closer to giving the program he created their proper recognition.

“We have long had a perspective that we have a future instilled for us, that’s what we’ve been told,” Oren said. “And everything is moving just right on time.”

• • •

Simmons Sr. knew he couldn’t get Oren registered as a student at Syracuse University unless he had a special skill beyond lacrosse. Being a high-quality athlete wasn’t going to justify accepting a 24-year-old seventh-grade dropout. Luckily for Simmons Sr., he received the best news possible.

Oren’s a masterful painter.

Since childhood, Oren’s been infatuated with art. He’s a master of sports illustrations, Rex said, centering most of his personal work around painting ancient Indigenous lacrosse players and Haudenosaunee war heroes. Simmons Sr. heard rumblings about Oren’s artistic side — he already knew about his on-field potential and past military service — and arrived on Onondaga Nation territory with an offer.

“Have you ever considered playing at Syracuse University?” Simmons Sr. asked Oren.

“Let me think about it,” he responded. “How’s that going to happen?”

“You just let me worry about that,” Simmons Sr. said. “In the meantime, I hear you’re an artist. Maybe we can get you in the art school.”

Art is one of Oren Lyons’ main passions away from the sport of lacrosse. Lyons specializes in cultural paintings that highlight his Indigenous heritage. Courtesy of Rex Lyons

Simmons Sr. doubled as SU’s boxing coach at the time. On off nights, he would visit The Ringside, a boxing-themed bar in Syracuse during the ‘50s. The owner of the now-defunct bar previously purchased some of Oren’s paintings, which depicted famous boxers.

So Simmons Sr. invited Dean Hefner, then-SU’s dean of admissions, out to lunch at the bar one afternoon. Simmons Sr. walked the two around the bar until they arrived at the paintings.

Simmons Sr. and Hefner stared at the boxer drawings in awe.

“The person who painted these must be kind of talented,” Simmons Sr. said.

“Yeah,” a stoic Hefner agreed, his mind fixated on the detailed brush strokes and rustic themes of the artwork.

“Well, I know the kid who painted them,” Simmons Sr. revealed. “And I’d like to get him into our school. He’s a great athlete, too.”

Art is why Oren became one of SU’s first Indigenous students — today, the university offers a variety of Indigenous scholarships. Art is also what helped Oren form his eloquence and it’s the talent that caused him to venture into the natural world, where humanity’s deeply-rooted flaws were confirmed to him.

Oren left the reservation in 1958 after graduating from SU and moved to New York City. For over a decade, Oren lived with his wife and kids across NYC and New Jersey, working as an artist and a lacrosse magazine founder.

He briefly worked for Norcross Greeting Cards, designing art for the company. But his artistic wonder was best displayed in his creation of Lacrosse International, the world’s first-ever lacrosse-focused print magazine. Carpenter said Oren taught the world how to play the sport through illustrations. He’d include drawings that explained how to execute certain moves like an over-the-head check or faceoff technique.

Carpenter said the magazine’s release was among the first major milestones to influence lacrosse’s modern-day growth.

And that’s often swept under the rug.

“Oren was the first lacrosse influencer,” Carpenter said. “This is not stuff that most people know.”

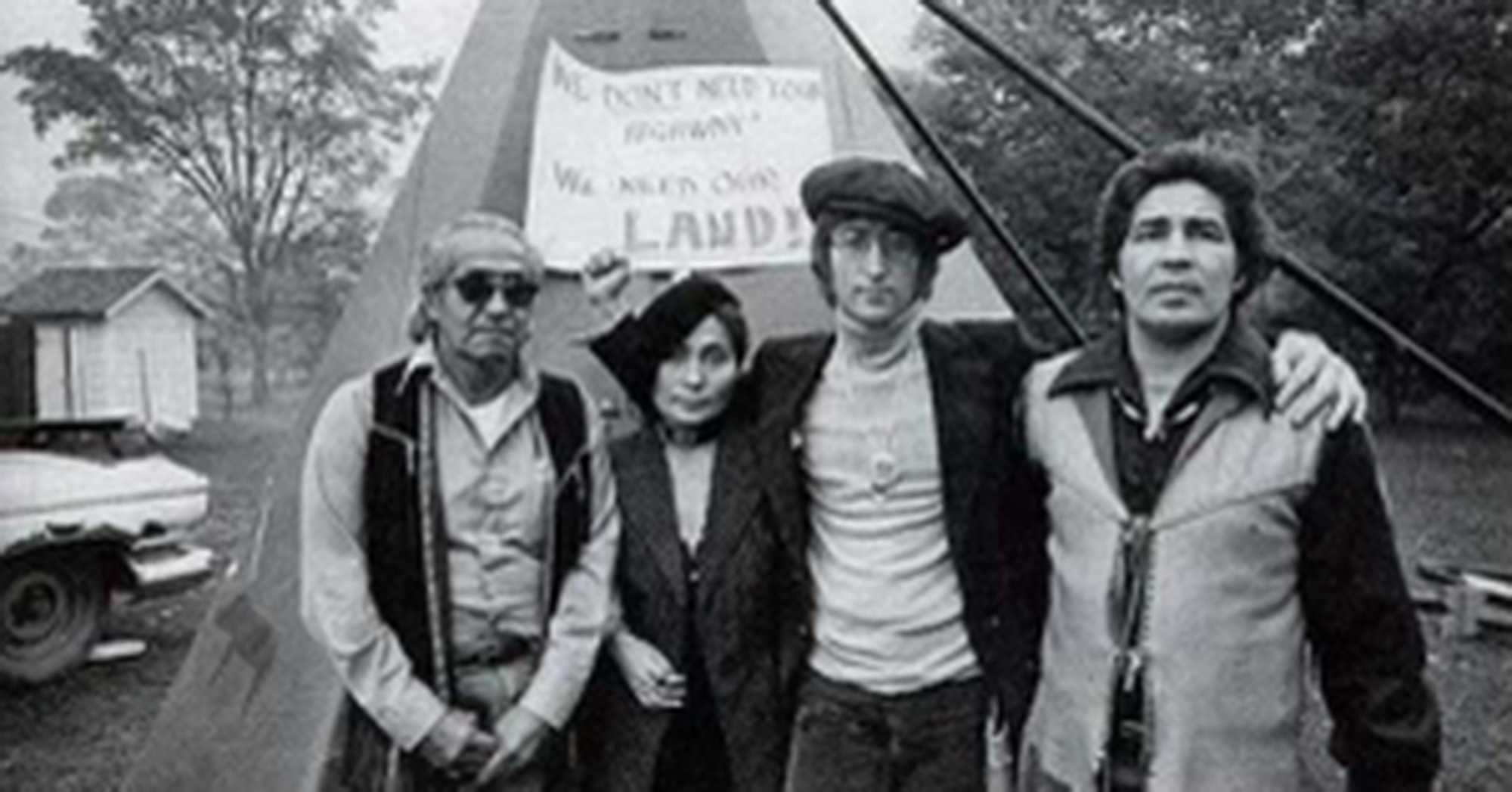

Oren Lyons (pictured, right) poses with John Lennon and Yoko Ono in 1971 during a protest against the expansion of Interstate 81 in New York state. The famous couple came to Syracuse because of an art exhibition Ono was holding at the Everson Museum of Art, and they wanted to help out Lyons. Courtesy of Rex Lyons

As much as art piqued his interest, Oren found it difficult to acclimate to the hustle, bustle and greed that engulfs NYC. He interacted with Wall Street men and saw the gluttonous underbelly that he believes American society glorifies. Then, as if fate hadn’t hit Oren enough times already, he got a knock on his front door.

Oren’s Clan Mother — Frieda Jacques — traveled to his house in New Jersey and begged him to return to his true home. The Haudenosaunee’s Wolf Clan was searching for a new Faithkeeper. At the time, because of their fight for Indigenous rights, there was uncertainty on the reservation. Oren was their No. 1 choice to lead them into a brighter future.

He proudly accepted. In his near-six decades of service, he’s hailed as one of the Haudenosaunee’s most impactful Faithkeepers, where his daily objective remains repairing mankind’s connection with nature.

“For him to come back and help with many of the things that we were challenged with at that time was really important,” Nolan said.

After returning to central New York, Oren’s artistic wisdom manifested itself through his showmanship when speaking before large audiences.

Rex, Betty and Nolan have many memories of being on the front lines with Oren passionately debating for Indigenous rights. They say he knows how to play people’s heartstrings.

Betty’s eyes still well up when she ponders a speech Oren gave at a U.N. summit a few years ago. They were there to advocate for sovereign expression and discuss the modern-day inequalities Indigenous people suffer from. Betty often helps Oren write his scripts. The night before the summit, the two stayed up all night to prepare. Betty estimates Oren works about 96 to 100 hours each week preparing for U.N. events.

So it took her by surprise when all their hard work went to waste by the next day.

“Oh my goodness,” Betty thought to herself as Oren began his address. “This is not the speech I typed out.”

Oren instead presented a recycled speech from almost two decades prior. In his diatribe, he fearlessly brought up the inaction certain U.N. member nations have shown over the years. He issued a reminder that, even while reading an address he’s already given before, he was still there to talk about the same problems Indigenous people face.

“I gave this speech back in 2004,” Oren told the leaders. “And still, the ice is melting. And you still do nothing about it.”

Tears streamed down Betty’s face when Oren delivered the punchline. She said the purity of Oren’s tone and the defiance of his message silenced the whole U.N. floor, a sign he successfully changed at least a few perspectives that day.

“He takes you on a ride,” Betty said of Oren’s speeches. “You’re going through these valleys, hills and around these turns. And then at the very end, it’s like you crash into a brick wall with how he ends it. It’s like you got punched in the face when you’re done.”

A soul-stirring picture only Oren can paint.

Collage by Ilana Zahavy | Presentation Director

Published on September 11, 2025 at 1:44 am