Opinion: Political absurdity isn’t an excuse to stop fact-checking media

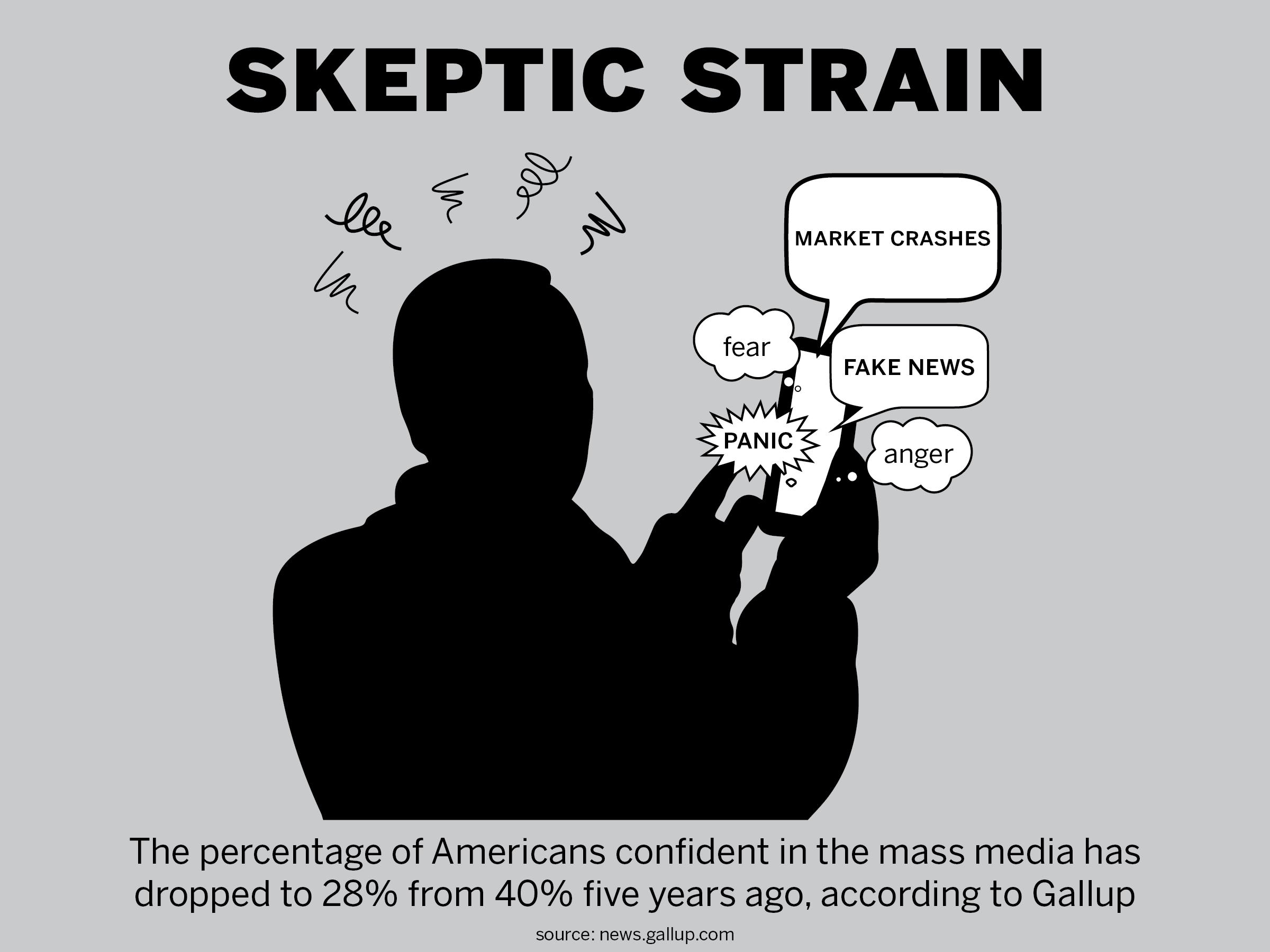

Mistrust in the media has made skepticism instinctive. When we stop seeking accuracy, our columnist warns, misinformation and half-truths will define how we understand governance and policy. Khloe Scalise | Contributing Illustrator

Get the latest Syracuse news delivered right to your inbox.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

A clip of White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt stating, “At this moment in time, of course, the ballroom is really the President’s main priority,” at an Oct. 23 White House briefing went viral overnight.

My feed flooded with TikTok edits and Instagram posts using the quote to comment on what many viewed to be the President Donald Trump administration’s misplaced priorities, alongside angry comments piling up faster than I could read.

When I saw the video, I paused mid-scroll. Shocked at the absurdity, I immediately searched for the original press recording.

In the full clip, a reporter asked whether Trump had plans for other renovations beyond the ballroom and the Rose Garden patio. Leavitt explained that, while she isn’t aware of additional projects, Trump is a “builder at heart” and is constantly thinking of improvements to the White House grounds.

“But at this moment in time, of course, the ballroom is really the President’s main priority,” she replied, and suddenly it made far more sense.

The full context was there all along, but that snippet was the only part that caught fire. Despite the clarity of the full recording, outrage erupted almost instantly. People reacted to a single line without pausing to consider the larger picture.

She wasn’t commenting on national policy or overall government priorities – she was simply responding to a question about renovations. But honestly, I can’t blame the internet for such a reaction.

Between the longest government shutdown in United States history and social programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program at risk, essential services are being left in limbo.

Millions of Americans, especially elderly and disabled individuals, rely on SNAP for basic nutrition. When the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced it could only guarantee partial benefit payments amid the shutdown, it wasn’t just a procedural delay – it was a reminder of how fragile government reliability can feel.

In a time when leadership appears disconnected from daily struggles, believing an outrageous comment about a ballroom somehow makes sense.

Outrage travels faster than truth because, in today’s political climate, the absurd feels expected. Politics have grown so polarized and unpredictable that our sense of what’s plausible keeps shifting. A press secretary identifying a ballroom as the president’s main priority might feel crazily out of touch – but so does a government shutdown that leaves millions uncertain about how they will put food on the table.

Even the headlines and images circulating the news seem to blur the line between reality and exaggeration. Late last month, Trump hosted a “Great Gatsby”-themed Halloween party at Mar-a-Lago, complete with champagne towers and 1920s costumes, just hours before SNAP funding deadlines loomed. The event went viral for its extravagance and how it felt almost dystopian watching the president throw a lavish party while millions faced economic uncertainty.

Katie Crews | Design Editor

The juxtaposition of luxury and dysfunction made the viral Leavitt clip feel eerily fitting, highlighting just how disconnected political leaders’ decisions can feel from the struggles of everyday Americans.

But the breakdown in trust runs deeper than any single viral clip. Over the past few years, edited videos, out-of-context clips and artificial intelligence have made skepticism instinctive.

A 2024 survey from Elon University found that 52% of Americans are not confident they can detect altered or faked audio, 47% can’t detect altered videos and 45% can’t detect faked photos.

Additionally, 73% believe it’s very or somewhat likely that AI will be used to manipulate social media to influence the outcome of the presidential election – through fake accounts, bots or distorted impressions of candidates. When misinformation can look and sound completely real, we learn to question everything, but not always in the right ways.

Many people didn’t pause to check the full recording of the Leavitt clip because the idea of a politician saying something so absurd seemed believable. We’ve been conditioned to expect the ridiculous, assuming that every day brings a new scandal or spectacle. But such collective fatigue has real consequences.

A 2024 Pew Research Center report revealed that only 22% of Americans said they trust the federal government “just about always” or “most of the time.” Trust in the media is similarly low, and as a result, many people check out politically altogether, scrolling past important updates or disengaging from their civic duties. When everything feels like a crisis, we stop asking questions because simply caring can feel exhausting.

The Leavitt clip illustrates this perfectly. It wasn’t just that a single line was taken out of context; it was that we’ve been conditioned to believe that anything from politicians is likely absurd, unrelatable or downright dystopian.

Between AI-generated content, viral clips and constant political turbulence, distinguishing reality from misinformation requires effort most of us aren’t willing to give.

But this doesn’t mean we have to completely give up and disengage. We can still approach news critically without retreating entirely. Watching full clips before sharing and fact-checking with several reputable sources are small but meaningful ways to resist the noise. The Leavitt clip should remind us not only how quickly outrage can spread but also how important it is to slow down and seek context.

The truth may take longer to uncover, but it’s well worth the effort. If we stop seeking accuracy, misinformation and half-truths begin to define how we understand governance, policy and the world around us.

Addy Kimball is a freshman majoring in political science. She can be reached at akimba02@syr.edu.