O

ne night in the early 1990s, seated on a plane heading back to Syracuse, Lawrence Moten grabbed a USAir magazine from the back of the chair in front of him and ripped off its cover. The page featured a photograph of two girls, one slightly taller than the other. It reminded Moten, then a young SU basketball star, of the daughters he yearned to raise one day. He’d already expressed his dreams of being a girl dad to his future wife, Noelene, so he stuffed the magazine cover in his carry-on to accelerate the inevitable.

When he returned to his house, a small place off campus he shared with Noelene, Moten embraced his then-girlfriend, walked her to their bedroom and showed her the cover. He then grabbed a marker off their desk and scribbled a caption on the image and turned to show Noelene. “Our daughters,” it read.

Noelene hung the magazine cover on their bedroom wall, where it remained until they graduated. At that moment, she knew Moten was the right man to start a family with.

Before the couple turned 30, they already had their pair of daughters: Lawrencia and Leilani, one slightly taller than the other.

“He planted the seeds for our future,” Noelene said. “We planned on being together forever. Not only in this life, but even in the next.”

Moten poured every ounce of energy he had into raising his girls. His warmth, honesty and vibrant spirit shaped their lives. That’s why accepting reality is difficult for them.

As Leilani, Moten’s youngest, grew older, she began referring to her dad as her “living legend.” Now she says she can’t anymore.

On Sept. 30, 2025, Moten died inside his home in Washington, D.C. He was 53.

Moten’s life as the leading scorer in Syracuse basketball history is only one part of his story. He was a family man first. If he rocked with you, as Noelene said, he brought you into his life without hesitation. The smooth-talking, high-sock-wearing hooper from D.C. was larger than life to those closest to him. Moten’s legacy as the man nicknamed “Poetry in Moten” is one of loyalty. One of perseverance. One of charity. One of love — pure, girl dad love.

What keeps the Moten family pushing through tragedy is their belief that their patriarch lived “a dream life,” a magnificent existence that touched countless others. Seeing over 5,000 people show up to Moten’s funeral in October — former teammates, friends, neighbors and relatives — made them realize Moten’s life should be celebrated, not mourned.

“It makes sense to me why he was taken,” Lawrencia said. “I think because God wanted somebody so great to be in heaven. He did so many amazing things on this Earth. My dad’s purpose was to change lives, and he did that.”

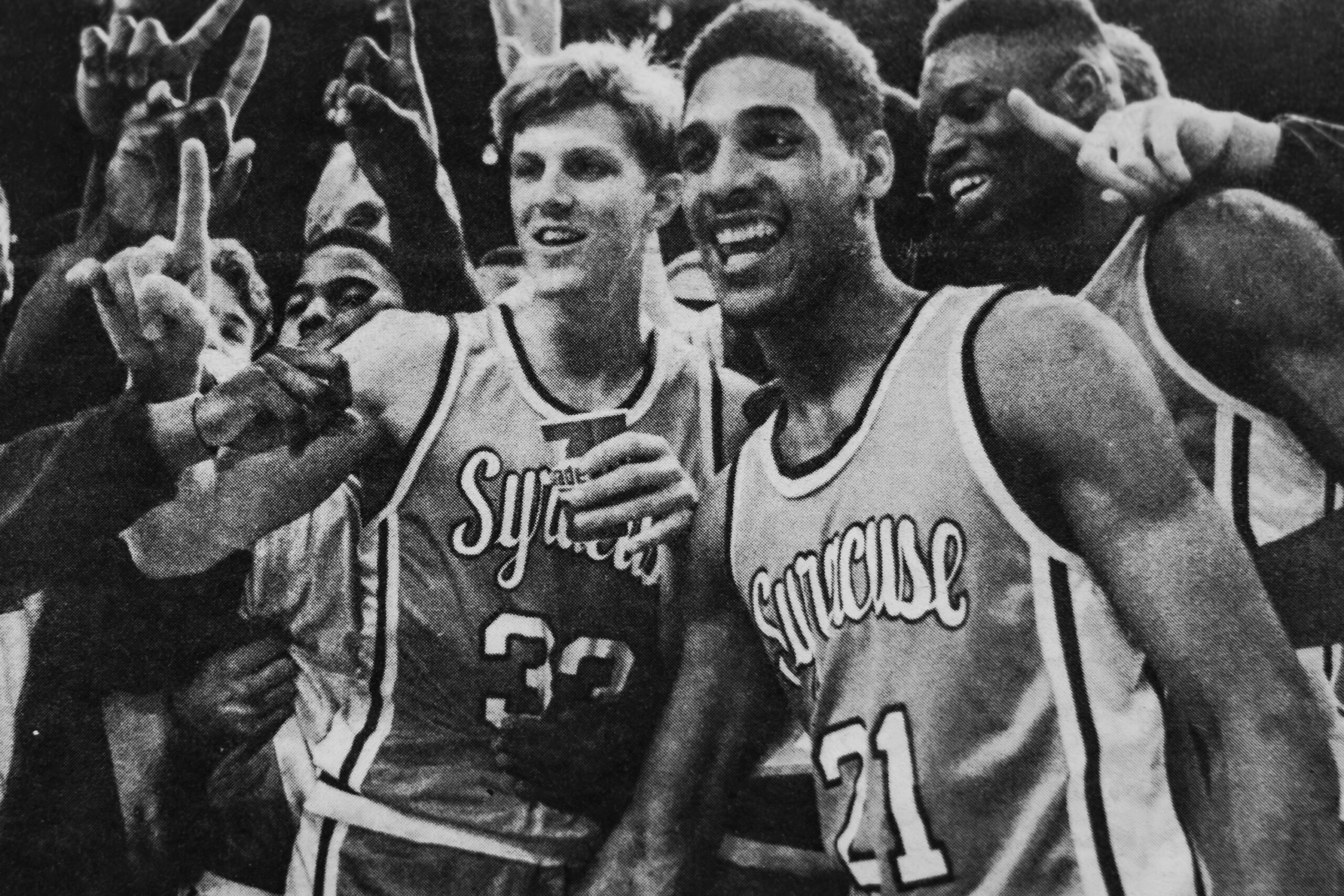

Surrounded by teammates, Lawrence Moten celebrates after a Syracuse win. Out of all the players he has coached, Jim Boeheim considered Moten the one he trusts most with the ball. Daily Orange File Photo

• • •

Moten revved the engine of his 1991 red Acura Legend and parked in front of John Wallace’s house. Little did they know that’d be the start of a four-year war.

It was freshman orientation week. Moten and Wallace had just met for the first time earlier in the day. Moten, the lowest-rated recruit of Syracuse’s six-man rookie class that season, challenged Wallace to a one-on-one at Thornden Park, looking to prove himself. Wallace, a 6-foot-8 Rochester native and highly-rated SU basketball recruit, uptook the offer.

Once they arrived, the two stepped on the court’s black asphalt. They stretched. They laced their shoes. Then Moten, after pulling his white socks up to his kneecaps, set the ground rules.

“First to 100,” he said.

“Shoot, alright,” Wallace answered.

Wallace’s size and brute strength matched up against Moten’s smooth shot and killer crossover made for a hotly-contested first battle. Moten won this one, 100-98. Wallace, bewildered, called for another game the next day. Then another. And another.

“He beat me the very first time we played, it was shocking to me. But that’s when you realize the greatness of Lawrence,” Wallace said. “His nickname is so fitting, because he looked like he was going so slow, but he wasn’t. The way he was able to maneuver and get angles on you, it was poetry.”

Moten squared off against Wallace in thousands of one-on-ones over their four years together at SU. The two now rank as Syracuse’s highest-scoring duo of all-time. But in hindsight, it was an unfair matchup for Wallace. From 1991-95, Moten racked up the most points in Syracuse men’s basketball history — 2,334 — and the most points in Big East history — 1,405.

Moten’s No. 21 jersey was retired in the JMA Wireless Dome rafters on March 3, 2018. He went on to play for the NBA’s then-Vancouver Grizzlies and Washington Wizards.

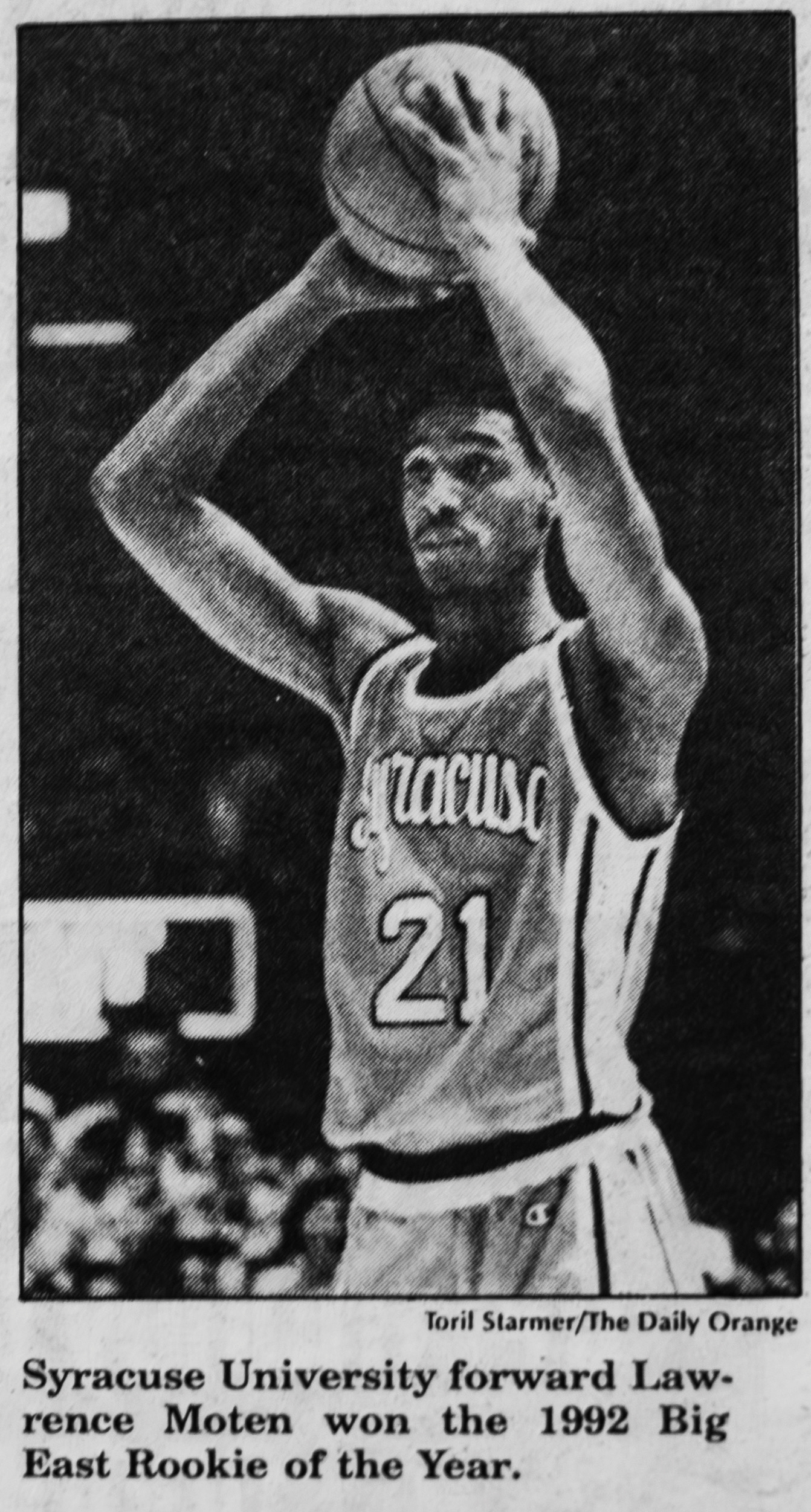

But Syracuse is where he truly made a name for himself. His four All-Big East Team selections, conference Rookie of the Year honor (1991-92) and career scoring average of 19.3 points per game is a collection of achievements that likely won’t be replicated again.

He even helped recruit Carmelo Anthony to Syracuse, per Noelene, who says he called Melo for about 30 minutes before his commitment and sold him on how he could become a legend at SU.

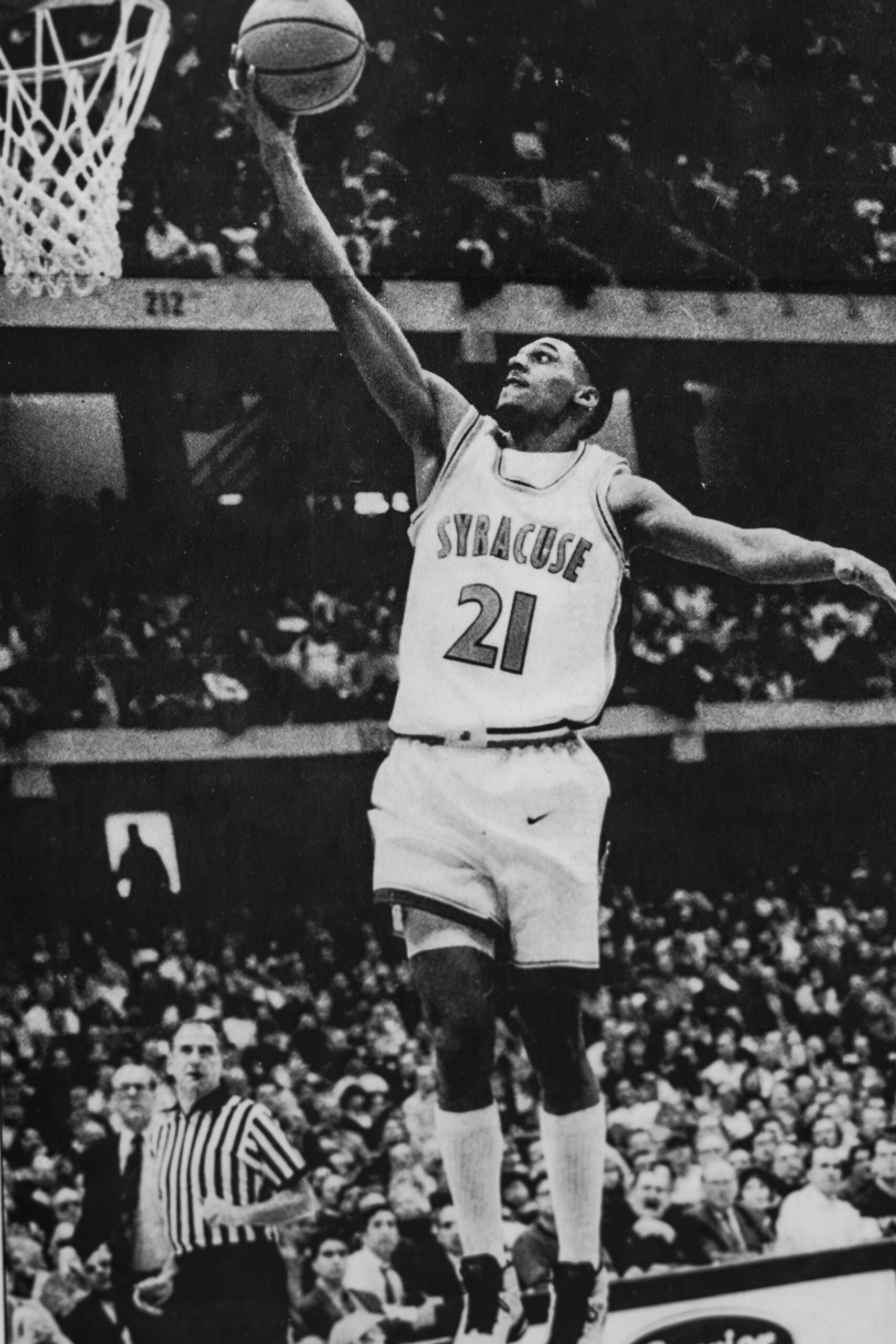

Moten’s legacy stands alone among the Orange’s all-time great hoopers, both for his place in the record books and for his signature silky-smooth playstyle — what teammates hailed as “Poetry in Moten” — that defined SU in the early ’90s.

“He’s the most underrated player that’s ever played here,” said Hall of Fame head coach Jim Boeheim, who helmed Syracuse from 1976 to 2023. “He’s in the top tier of players I ever coached. He made it look so easy.”

Moten grew up in D.C. playing basketball and football. Boeheim said Moten was probably a better football player before coming to SU, but he chose basketball.

An old Daily Orange newspaper clipping from Lawrence Moten’s 1992 Big East Rookie of the Year. Despite joining the Orange as their lowest-rated recruit in the class of 1991, Moten quickly established himself as a starter. Daily Orange File Photo

He came to Syracuse as one of six freshmen in Boeheim’s 1991 class, along with Wallace, Anthony Harris, Glenn Sekunda, Stephen Keating and Luke Jackson. All five were ranked above Moten. But, as a freshman, he played more than all of them combined.

His road to glory began in Atlanta on Dec. 3, 1991, against Florida State. After a standout preseason camp where he drained shots and exerted stout defense, Boeheim said, Moten finally earned his first start.

Jackson said the freshmen on the bench looked at each other in amazement when Moten took the floor with a fiery gaze and his white socks pulled to his knees — a signature D.C. hooper’s look.

“Here comes the separation,” Jackson recalled saying from SU’s bench.

Moten dropped 18 points on 8-of-13 shooting in 36 minutes, helping the Orange to a 89-71 victory. He never looked back, winning Big East Rookie of the Year honors and evolving into Boeheim’s most trusted player with the ball in his hands.

As the years went on at SU, Moten’s confidence grew. He’d let you hear it, too. Moten, a mild-mannered man away from the court, had a killer instinct on the hardwood. You could tell Moten locked in when his voice got high-pitched, said Jackson and fellow teammate Adrian Autry, now Syracuse’s head coach.

It was frightening to hear, Jackson said, when Moten’s voice picked up a tune during practice. He got into others’ heads just by stating the obvious in a condescendingly squeaky tone.

“They can’t guard me, mannnn,” Michael Lloyd, Moten’s teammate in 1994-95, recalled Moten telling opponents. “And he’d have those sneaky little quotes he’d be saying like, ‘Twenty-four and five. I’m gonna give him 24 (points) and five (rebounds).’ He wasn’t real sneaky with it. He’d be like, ‘That’s gonna be all night.’”

“He was cocky but not arrogant,” added Lazarus Sims, who played with Moten at SU from 1992-95. “I’d try to get under his skin, and then he’d be in practice tearing Mike (Hopkins) up or Luke Jackson. Then it’d be me. I’d be like, ‘Man, why you doing this to me?’”

It was all in good fun, of course. Moten had the authority to boss his teammates around a bit, as long as they brought their all on the floor together. They all knew he was unstoppable, with his long arms, precise shot and deceptive speed making him an offensive weapon. So they didn’t get too bothered by Moten schooling them in practice.

He encouraged them plenty. One time in a game against UConn, Hopkins missed a free throw. Rather than giving him the old clap on the hand, Moten walked over and kissed Hopkins on the cheek. That was his way of telling Hopkins to move on to the next one.

“If you don’t like Lawrence, something’s wrong with you,” Autry said.

Moten looked out for his guys away from the court, too.

He showed Lloyd how to get to his classes. He showed Sims around campus and gave him an immediate role model, despite being his peer. He even gave Todd Burgan an unforgettable moment, one that allowed him to acclimate to a new environment he was hesitant to enter.

Waiting for a bus at College Place early in the fall of 1994, Burgan was surrounded by throngs of strangers competing for a spot on the next bus. Burgan, who finished his high school career at New Hampton Prep — Moten’s alma mater — looked up to the prolific scorer as a hero. Now, he was his teammate.

Luckily for Burgan, Moten — then a senior — rolled up to the bus stop in his sportscar, eliciting oohs and ahhs from the students around him. They knew it was the king.

“Of course I see him, but I don’t know if he has something to do,” Burgan said. “It’s a bus stop full of people.”

Moten singled out Burgan.

“Get in, man,” Moten directed Burgan, who happily obliged and got a ride home.

“I mean, come on. It’s Lawrence Moten,” Burgan said. “That’s my big brother.”

Lawrence Moten reaches up his arm to slam home a dunk. Moten was renowned for his silky smooth playstyle, earning him the nickname, “Poetry in Moten.” Daily Orange File Photo

• • •

On occasion, Leilani opens her iMessage history with her father and reads heartwarming texts from him. He never went a day without telling her “good morning,” “good night,” “I love you” and a few inspirational one-liners, too.

There’s a message from 2021 that Leilani keeps circling back to. Leilani didn’t follow a similar path to her father or older sister. She didn’t play college athletics like Moten and Lawrencia did, and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in finance from Morgan State University — the first in her family to attend an HBCU.

Sometimes, Leilani felt uneasy about venturing away from sports. Finance isn’t an industry where she has many Black women colleagues, Leilani said, and she didn’t know how Moten would feel about how she’d fit in. But all Moten cared about was his daughters’ fulfillment. He reminded Leilani of this repeatedly. After she got a job with Chase as a leadership development analyst in the summer of 2021, Moten couldn’t wait to congratulate her.

“Just wanted you to know that I’m extremely proud of you and what you have accomplished so far in your life. Keep following your dreams. Stay positive and passionate. You are a shining light. Keep pushing for your own greatness, I love you. Every day is an audition,” the text reads.

That last line was something Moten lived by, Leilani said. If you treat every day as an audition, her father would say, doing your best will consistently reward you. Nowadays, Lawrencia, a sports broadcaster, and Leilani, a financial advisor for Merrill Lynch Wealth Management, are thriving in their upper-20s, success they credit to their father’s unconditional support.

By all accounts, Moten’s greatest achievement was raising his daughters. And his daughters’ greatest experience was knowing their father.

“It wasn’t tough love, it was the opposite. It was true love,” Lawrencia said of how her father parented her. “He was so caring and so connected with us. He was a girl dad through and through.”

Moten’s journey to fatherhood began when he found Noelene. In her freshman year at SU, Noelene met Moten in the spring of 1991, while he was a high-school senior on a recruiting visit to Syracuse. The two locked eyes when they passed each other on campus. Noelene thought Moten — sporting his jet black high-top fade and flashing an inviting smile — was cute.

That fall, Noelene was in the middle of the Quad when she first heard her soulmate calling her name.

“Noeeee-” Moten shouted across the Quad.

“Oh my goodness, he actually came,” Noelene blushed.

They hit it off. Noelene was committed to Moten’s lifestyle. They went long distance several times, including when Moten played for the Vancouver Grizzlies, but that never derailed them.

“Once we stepped out of the friendship zone, there was no ever going back,” Noelene said. “We had to be together by any means necessary.”

Noelene admired Moten’s kindness and generosity, as well as his ability to make everyone around him feel at home. Looking back, she can’t think of her husband’s death without realizing how lucky she was to be in the majority of his life.

Lawrence Moten stands alongside his wife, Noelene. Moten met Noelene while visiting Syracuse during his recruitment, and the two were inseparable from then on. Courtesy of Lawrencia Moten

“I had a moment — ‘Oh my gosh, I was married to an angel,’” Noelene said. “I didn’t realize all this time. I really feel like he was an agent for God, and that’s why he’s gone so soon.”

The angel Noelene speaks of was as much involved with waking the kids up for school, making dinner and taking the girls to basketball practice as she was. Moten woke up and planned out the whole day for the family, she said, beaming ear to ear each second he could spend with Lawrencia and Leilani.

He took them on picnics, to D.C. museums and zoos, out to eat Maryland soft-shell crab, to sporting events and parks, anywhere they wanted to go. At home, he was a ball of energy that could make any sad day a good one. He always danced to whatever music he blared across the living room — Moten loved groovy go-go music artists like Chuck Brown. And he’d entertain his daughters by playing Just Dance on the Wii with them. They’d laugh for hours watching their father’s silly dance moves to pop songs. He’d always win, too.

Moten was fun when he needed to be fun, and serious when he needed to be serious.

Growing up, his mother, Lorraine Burgess, always told him a phrase: “Don’t just stand up on the hill.” It meant to have a drive to succeed in all facets of life, even when the going seems tough.

For Leilani, she said she couldn’t have gone on to find stability for herself in an unknown field without her father reinforcing positivity into her and the direction she’d chosen. Moten expected his daughters to follow their own legacy, and never stopped believing they’d reach their full potential.

“We were always pouring love into each other, we never stopped pouring into each other,” Leilani said. “That’s why this is still so unbelievable. And we’re having a difficult time accepting it, because the roots are so deeply-planted with him.”

Moten’s words also advanced Lawrencia’s journalism aspirations. She’s worked in sports broadcasting for a few years after graduating from the University of Hartford, where she also played basketball, and wants to venture into other areas, like entertainment reporting.

But having her father’s blessing to hang up her basketball shoes gave her the confidence to jump into journalism headfirst.

“That’s something we can all take away from (him) — even when you’re dropping 30 (points) on the court, you can still make everyone feel loved,” Lawrencia said of her dad. “If we all do that more, the world would be a better place.”

Moten’s work outside parenting was philanthropic. He founded the Willow Street Foundation to help financially disadvantaged children in Syracuse. From at home to out in the world, there was never a time Moten wasn’t trying to do what his mother did for him — set kids on a stable path forward.

Moten serves as an everlasting example of how to be a good dad. His close pals, who are also fathers, grew inspired by him.

Romeo Roach, Moten’s best friend from the D.C. area, would see the way Moten raised his daughters and incorporate it into his own parenting. The time, the care, the unconditional love, the acceptance and unwavering encouragement he had for their personal choices — Moten’s parenting style was rare.

“I’m trying to do what he was doing with his daughters with my kids,” Roach said. “His girls were his number one.”

“They say Kobe Bryant was the ultimate girl dad. Mo’s got him beat by one thousand,” added Sims, who said Moten’s way of never judging his daughters for anything is something he’s applied to his own parenting.

More than anything, all a kid wants from their parents is to hear them say they’re proud. With Lawrencia and Leilani, it was never a question.

Whether a simple text, a congratulatory hug or a heartfelt paragraph to congratulate Leilani on becoming the first in their family to attend an HBCU, Moten never failed to remind his daughters he loved them. Even in death, the girls can still feel their father’s pride.

“I’ll never have to guess how proud he was of me,” Lawrencia said.

Lawrence Moten stands alongside his two daughters, Leilani and Lawrencia. Moten was remembered as a devoted father, even inspiring friends to change their parenting styles. Courtesy of Lawrencia Moten

• • •

When Moten died, he still flashed a six-pack of abs. He could still dunk a basketball. He was in an unbreakable spirit. He was texting his daughters daily; calling friends weekly.

This was a man who many saw as superhuman. Yet, far too often, his friends and family are reminded of their worst memory of Moten — the day their world stopped.

“I still can’t quite wrap my arms around it right now,” Boeheim said of Moten’s death. “It was unfathomable. Life happens sometimes. I just can’t understand it.”

Among all his former teammates, the memories hit particularly hard for Wallace, who became as close to an uncle to Moten’s children as a non-blood relative could be. Every now and then, when walking through his house, Wallace spots the invitation he received for Moten’s funeral service. For him, Sept. 30, 2025, feels like yesterday.

That morning, Wallace was driving back home to Rochester from New York City. He received a text from Burgan. Wallace checked his phone, making sure it wasn’t anything urgent. But he refused to believe what he read.

Wallace called Lloyd, knowing he must’ve been in recent contact with Moten. Lloyd confirmed the news. Wallace flicked his turn signal and pulled off to the right side of the road on Interstate-81. His mind turned to Moten’s daughters. Lawrencia was the first to pick up, and the two sobbed on the phone for a while.

Nothing could change Wallace’s disbelief in the moment. He still took the time to comfort his unofficial niece during her darkest hour — because that’s what Moten would do.

Teamwork, one last time.

“My brother’s not here,” Wallace often reminds himself. “He was in such good shape. It’s just crazy.”

Design by Adelaide Guan | Design Editor

Daily Orange File Photo, Courtesy of Lazarus Sims, Courtesy of John Wallace, Courtesy of Lawrencia Moten

Published on January 29, 2026 at 1:30 am